In this article, we are going to learn all about the communication skills. Here, we will provide the easy and helpful steps to improve your communications skills in the English language. Read the entire article and enhance your communication skills. Here, we will talk about:

- What is communication?

- The transmission model.

- Understanding how we understand.

- A new model of communication.

- The three levels of understanding.

- Conversation: the heart of communication.

What is communication?

It’s a question I often ask at the start of training courses. How would you define the word ‘communication’? After a little thought, most people come up with a sentence like this.

Communication is the act of transmitting and receiving information.

This definition appears very frequently. We seem to take it for granted. Where does it come from? And does it actually explain how we communicate at work?

The Transmission Model

That word ‘transmitting’ suggests that we tend to think of communication as a technical process. And the history of the word ‘communication’ supports that idea.

In the 19th century, the word ‘communication’ came to refer to the movement of goods and people, as well as of information. We still use the word in these ways, of course: roads and railways are forms of communication, just as much as speaking or writing. And we still use the images of the industrial revolution – the canal, the railway and the postal service – to describe human communication. Information, like freight, comes in ‘bits’; it needs to be stored, transferred and retrieved. And we describe the movement of information in terms of a ‘channel’, along which information ‘flows’.

This transport metaphor was readily adapted to the new, electronic technologies of the 20th century. We talk about ‘telephone lines’ and ‘television channels’. Electronic information comes in ‘bits’, stored in ‘files’ or ‘vaults’. The words ‘download’ and ‘upload’ use the freight metaphor; e-mail uses postal imagery.

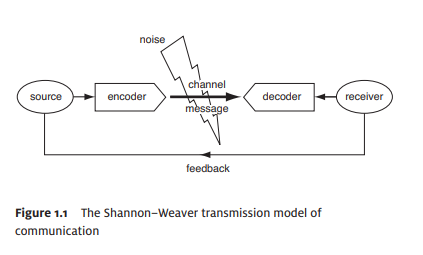

In 1949, Claude Shannon and Warren Weaver published a formal version of the transmission model (Shannon, Claude E and Weaver, Warren, A Mathematical Model of Communication, University of Illinois Press, Urbana, IL, 1949). Shannon and Weaver were engineers working for Bell Telephone Labs in the United States. Their goal was to make telephone cables as efficient as possible.

Their model had five elements:

- an information source, which produces a message;

- a transmitter, which encodes the message into signals;

- a channel, to which signals are adapted for transmission;

- a receiver, which decodes the message from the signal; and

- a destination, where the message arrives.

They introduced a sixth element, noise: any interference with the message travelling along the channel (such as ‘static’ on the telephone or radio) that might alter the message being sent. A final element, feedback, was introduced in the 1950s.

For the telephone, the channel is a wire, the signal is an electrical current, and the transmitter and receiver are the handsets. Noise would include crackling from the wire. Feedback would include the dialling tone, which tells you that the line is ‘live’.

In a conversation, my brain is the source and your brain is the receiver. The encoder might be the language I use to speak with you; the decoder is the language you use to understand me. Noise would include any distraction you might experience as I speak. Feedback would include your responses to what I am saying: gestures, facial expressions and any other signals I pick up that give me some sense of how you are receiving my message.

We also apply the transmission metaphor to human communication. We ‘have’ an idea (as if it were an object). We ‘put the idea into words’ (like putting it into a box); we try to ‘put our idea across’ (by pushing it or ‘conveying’ it); and the ‘receiver’ – hopefully – ‘gets’ the idea. We may need to ‘unpack’ the idea before the receiver can ‘grasp’ it. Of course, we need to be careful to avoid ‘information overload’.

The transmission model is attractive. It suggests that information is objective and quantifiable: something that you and I will always understand in exactly the same way. It makes communication seem measurable, predictable and consistent: sending an e-mail seems to be evidence that I have communicated to you. Above all, the model is simple: we can draw a diagram to illustrate it.

But is the transmission model accurate? Does it reflect what actually happens when people communicate with each other? And, if it’s so easy to understand, why does communication – especially in organisations – so often go wrong?

Wiio’s Laws

We all know that communication in organisations is notoriously unreliable. Otto Wiio (born 1928) is a Finnish Professor of Human Communication. He is best known for a set of humorous maxims about how communication in organisations goes wrong. They illustrate some of the problems of using the transmission model.

- Communication usually fails, except by accident. If communication can fail, it will fail.

- If communication cannot fail, it still usually fails.

- If communication seems to succeed in the way you intend – someone’s misunderstood.

- If you are content with your message, communication is certainly failing.

- If a message can be interpreted in several ways, it will be interpreted in a manner that maximises the damage.

- There is always someone who knows better than you what your message means.

- The more we communicate, the more communication fails.

Problems with the Transmission Model

What’s wrong with the transmission model? Well, to begin with, a message differs from a parcel in a very obvious way. When I send the parcel, I no longer have it; when I send a message, I still have it. But the metaphor throws up some other interesting, rather more subtle problems.

Do We Communicate What We Intend?

The transmission model assumes that communication is always intentional: that the sender always communicates for a purpose, and always knows what that purpose is. In fact, most human communication mixes the intentional and the unintentional. We all know that we communicate a great deal without meaning to, through body language, eye movement and tone of voice.

The transmission model also assumes that the intention and the communication are separate. First we have a thought; then we decide how to encode it. In reality, we may not know what we are thinking until we have said it; the act of encoding is the process of thinking. Many writers, for example, say that they write in order to work out what their ideas are.

What’s the Context?

A message delivered by post will have a very different effect to a message delivered vocally, face-to-face. Our response to the message will differ if it’s delivered by a senior manager or by a colleague. Our state of mind when we hear or read the message will affect how we understand it. And so on.

A One-Way Street

The transmission model is a linear. The source actively sends a message; the destination passively receives it. The model ignores the active participation of the ‘receiver’ in generating the meaning of the communication.

What does it all mean?

The transmission model ignores the way humans understand. Human beings don’t process information; they process meanings.

For example, the words ‘I’m fine’ could mean:

• ‘I am feeling well’;

• ‘I am happy’;

• ‘I was feeling unwell but am now feeling better’;

• ‘I was feeling unhappy but now feel less unhappy’;

• ‘I am not injured; there’s no need to help me’;

• ‘Actually, I feel lousy but I don’t want you to know it’;

• ‘Help!’

– or any one of a dozen other ideas. The receiver has to understand the meaning of the words if they are to respond appropriately; but the words may not contain the speaker’s whole meaning.

There is a paradox in communicating. I cannot expect that you will understand everything I tell you; and I cannot expect that you will understand only what I tell you.

If we want to develop our communication skills, we need to move beyond the transmission model. We need to think about communication in a new way. And that means thinking about how we understand.

Understanding How We Understand

Understanding is essentially a pattern-matching process. We create meaning by matching external stimuli from our environment to mental patterns inside our brains.

The human brain is the most complex system we know of. It contains 100 billion neurons (think of a neuron as a kind of switch). The power of the brain lies in its networking capacity. The brain groups neurons into networks that ‘switch on’ during certain mental activities. These networks are infinitely flexible: we can alter existing networks, and grow new ones. The number of possible neural networks in one brain easily exceeds the number of particles in the known universe.

The brain is a mighty networker; but it is also an amazing processor. My computer is a serial processor: it can only do one thing at a time. We can describe the brain as a parallel processor. It can work on many things at once. If one neural circuit finishes before another, it sends the information to other networks so that they can start to use it.

Parallel processing allows the brain to develop a very dynamic relationship with reality. Think of it as ‘bottom-up’ processing and ‘top-down’ processing.

• Bottom-up processing: The brain doesn’t recognise objects directly. It looks for features, such as shape and colour. The networks that look for features operate independently of each other, and in parallel. ‘Bottomup’ processing occurs, appropriately, in the lower – and more primitive – parts of the brain, including the brain stem and the cerebellum. The neural networks in these regions send information upwards, into the higher regions of the brain: the neo-cortex.

• Top-down processing: Meanwhile, the higher-level centres of the brain – in the neo-cortex, sitting above and around the lower parts of the brain – are doing ‘top-down’ processing: providing the mental networks that organise information into patterns and give it meaning. As you read, for example, bottom-up processing recognises the shapes of letters; top-down processing provides the networks to combine the shapes into the patterns of recognisable words.

When the elements processed bottom-up have been matched against the patterns supplied by top-down processing, the brain has understood what’s out there.

Top-down and bottom-up processing engage in continuous, mutual feedback. It’s a kind of internal conversation within the brain. Bottom-up processing constantly sends new information upwards so that the higher regions can update and adjust their neural networks. Meanwhile, top-down processing constantly organises incoming information into new or existing patterns.

The brain often has to make a calculated guess about what it has perceived. Incoming information is often garbled, ambiguous or incomplete. How can my brain distinguish your voice from all the other noise in a crowded room? Or a flower from a picture of a flower? How does it recognise a tune from just a few notes?

Top-down processing often completes incoming information by using pre-existing patterns. The brain creates a mental model: a representation of reality, created by matching incomplete information to learned patterns in the brain.

Visual illusions demonstrate how the brain makes these calculated guesses. In the image in Figure 1.2, for example, we appear to see a white triangle, even though the image contains no triangle. The brain’s top-down processing completes the incoming information by imposing a ‘triangle’ pattern – its best guess of what is there. (The triangle is named after Gaetano Kanizsa, an Italian psychologist and artist, founder of the Institute of Psychology of Trieste.)

We can call this process ‘perceptual completion’, and it’s not limited to visual information. Perceptual completion shows that all understanding is a ‘best guess’.

A New Model of Communication

What does all this mean for communication?

To begin with, the most important question we can ask when we are communicating is:

‘What effect am I having?’

How does the information we are giving relate to the other person’s mental models? What meaning do they attach to our behaviour, our words, gestures and voice? But we can go further. The pattern-matching model of communication suggests three important principles.

First, communication is continuous. If we are always updating our understanding, then communication needs to be continuous to be effective: not a one-off event, like a radio transmission, but a process.

Second, communication is complicated. Whatever we understand, has been communicated. That means everything we observe: not just the words someone speaks, but the music of their voice and the dance of their body. Some of the signals we send out are intentional; very many are not. We communicate if we are being observed.

We cannot not communicate.

(Paul Watzlawick, Mental Research Institute, Palo Alto, California)

Third, communication is contextual. It never happens in isolation. The meaning of the communication is affected by at least five different contexts.

• Psychological: who you are and what you bring to the communication; your needs, desires, values and beliefs.

• Relational: how we define each other and behave in relation to each other; where power or status lies; whether we like each other (this context can shift while we are communicating).

• Situational: the social context within which we are communicating; the rules and conventions that apply in different social conditions (interaction in a classroom or office will differ from interaction in a bar or on a sports field).

• Environmental: the physical location; furniture, location, noise level, temperature, season, time of day, and so on.

• Cultural: all the learned behaviours and rules that affect the way we communicate; cultural norms; national, ethnic or organisational conventions.

These insights suggest a different model of the communication process. In this model, we are at the centre of two interlocking sets of contexts, seeking to find common ground. Whatever we understand, we have communicated with each other.

Communication succeeds when we increase the area of common understanding (the shaded area in the diagram in Figure 1.3).

We need a new definition of the word ‘communication’. And the history of the word itself gives us a clue. ‘Communication’ derives from the Latin communis, meaning ‘common’, ‘shared’. It belongs to the family of words that includes communion, communism and community. When we communicate, we are trying to match meanings.

Or, to put it another way:

Communication is the process of creating shared understanding.

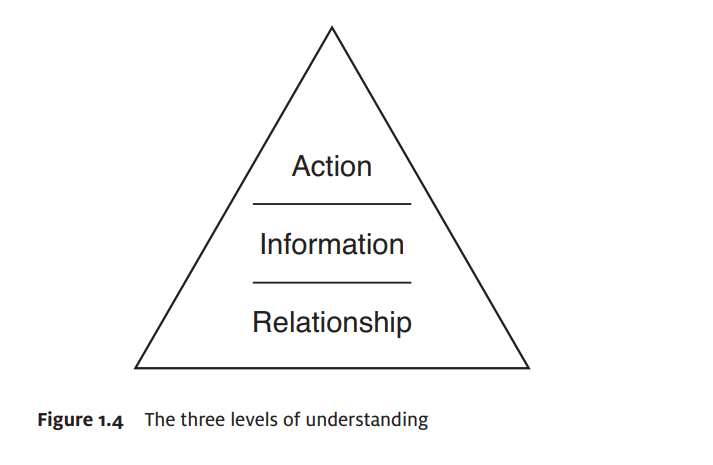

The Three Levels of Understanding

Communication creates understanding on three levels, each underpinning the one above (Figure 1.4).

As managers, we tend to focus on action as the reason for communicating. Yet, as people, we usually communicate for quite another reason. And here is a vital clue to explain why communication in organisations so often goes wrong.

Relationship: The Big Issue of Small Talk

The first and most important reason for communicating is to build relationships with other people. Recent research (commissioned from the Social Issues Research Centre by British Telecom) suggests that about two thirds of our conversation time is entirely devoted to social topics: personal relationships; who is doing what with whom; who is ‘in’ and who is ‘out’, and why. There must be a good reason for that.

According to psychologist Robin Dunbar, language evolved as the human equivalent of grooming, the primary means of social bonding among other primates. As social groups among humans became larger (the average human network is about 150, compared to groups of about 50 among other primates), we needed a less time-consuming form of social interaction. We invented language as a way to square the circle. In Dunbar’s words: ‘language evolved to allow us to gossip’ (Grooming, Gossip and the Evolution of Language, Faber and Faber, London, 1996).

Gossip is good for us. It tells us where we sit in the social network. And that makes us relax. Physical grooming stimulates production of endorphins – the body’s natural painkilling opiates – reducing heart rate and lowering stress. Gossip probably has a similar effect. In fact, the research suggests that gossip is essential to our social, psychological and physical well-being.

We ignore this fundamental quality of conversation at our peril. If we fail to establish a relaxed relationship, everything else in the conversation will become more difficult.

Building Rapport

The first task in any conversation is to build rapport. Rapport is the sense that another person is like us. Building rapport is a pattern-matching process. Most rapport-building happens without words: we create rapport through a dance of matching movements, including body orientation, body moves, eye contact, facial expression and tone of voice.

Human beings can create rapport instinctively. Yet these natural dance patterns can disappear in conversations at work; other kinds of relationship sometimes intrude. A little conscious effort to create rapport at the very start of a conversation can make a huge difference to its outcome.

We create rapport through:

• verbal behaviour;

• vocal behaviour; and

• physical behaviour

Of those three elements, verbal behaviour – the words we use – actually contributes least to building rapport.

Overwhelmingly, we believe what we see. In the famous sales phrase, ‘the eye buys’. If there is a mismatch between a person’s words and their body language, we instantly believe what the body tells us. So building rapport must begin with giving the physical signs of being welcoming, relaxed and open.

The music of the voice is the second key factor in establishing rapport. We can vary our pitch (how high or low the tone of voice is), pace (the speed of speaking) and volume (how loudly or softly we speak). Speak quickly and loudly, and raise the pitch of your voice, and you will sound tense or stressed. Create vocal music that is lower in tone, slower and softer, and you will create rapport more easily.

But creating rapport means more than matching body language or vocal tone. We must also match the other person’s words, so that they feel we are ‘speaking their language’.

————————————————————————

Building rapport: a doctor’s best practice

Dr Grahame Brown is a medical consultant who wondered why his sessions with patients were so ineffective. He began to realise that the problem was the way he conducted the interview. Getting the relationship right is, he believes, the key to more effective treatment.

My first priority now is to build rapport with the patient in the short time I have with them.

Instead of keeping the head down over the paperwork till a prospective heartsick patient is seated, then greeting them with a tense smile (as all too many doctors do), I now go out into the waiting room to collect patients whenever possible. This gives me the chance to observe in a natural way how they look, how

they stand, how they walk and whether they exhibit any ‘pain behaviours’, such as sighing or limping.

I shake them warmly by the hand and begin a conversation on our way to the consulting area. ‘It’s warm today, isn’t it? Did you find your way here all right? Transport okay?’ By the time we are seated, the patient has already agreed with me several times. This has an important effect on our ensuing relationship – we are already allies, not adversaries…

Next, rather than assuming the patient has come to see me about their pain, I ask them what they have come to see me about. Quite often they find this surprising, because they assume that I know all about them from their notes. But even though I will have read their notes, I now assume nothing. I ask open-ended questions that can give me the most information – the facts which are important to them.

(From Griffin, Joe and Tyrrell, Ivan, Human Givens, HG Publishing, Brighton, 2004)

————————————————————————

For most of us, starting a conversation with someone we don’t know is stressful. We can be lost for words. ‘Breaking the ice’ is a skill many of us would dearly love to develop.

The key is to decrease the tension in the encounter. Look for something in your shared situation to talk about; then ask a question relating to that. The other person must not feel excluded or interrogated, so avoid:

• talking about yourself; and

• asking the other person a direct question about themselves

Doing either will increase the tension in the conversation. As will doing nothing! So take the initiative. Put them at ease, and you will soon relax yourself.

————————————————————————

Learning the art of Conversation

1. Copy the other person’s body language to create a ‘mirror image’.

2. Ask three questions – but no more until you have done the next two things.

3. Find something from what you have just learned that will allow you to compliment the other person – subtly.

4. Find something in what you have found out to agree with.

5. Repeat until the conversation takes on a life of its own.

(With thanks to Chris Dyas)

————————————————————————

Information: displaying the shape of our thinking

Once we have created a relaxed relationship, we are ready to share information. So what is information, and how does it operate?

Every time we communicate, information changes shape. Children have enormous fun playing with the way information can alter in the telling. Chinese Whispers and Charades are both games that delightfully exploit our capacity to misunderstand each other.

Understanding – as we’ve already seen – is mental patternmatching. ‘Ah!’ we exclaim when we’ve understood something, ‘I see!’ We may have a different perspective on a problem from a colleague; we often misunderstand each other because we are approaching the issue from different angles. If we disagree with someone, we may say that we are looking at it differently. It’s all about what patterns we recognise: which patterns match our mental models.

Information is the shape of our thinking. We create information inside our heads. Information is never ‘out there’; it is always, and only ever, in our minds. And the shape of information constantly changes, evolving, as we think. Information is dynamic.

Action: influencing with our ideas

As well as creating relationships and sharing information, we communicate to promote action. And the key to effective action is not accurate information but persuasive ideas.

Ideas give meaning to information. Put simply, an idea says something about the information. A name is not an idea. These phrases are all names but, for our purposes, they aren’t ideas:

• Profit analysis;

• Asian market;

• Operations Director

To turn them into ideas, we have to create statements about them:

• Profit analysis shows an upturn in sales of consumables over the last year.

• The Asian market has become unstable.

• Bill Freeman is now Operations Director.

These sentences create meaning by saying something about the names. What we have done is very simple: we have created sentences.

An idea is a thought expressed as a sentence.

Ideas are the currency of communication. We are paid for our ideas. When we communicate, we trade ideas. Like currency, ideas come in larger or smaller denominations: there are big ideas, and little ideas. We can assemble the little ones into larger units, by summarising them. Like currencies, ideas have a value and that value can change: some ideas become more valuable as others lose their value. We judge the quality of an idea by how meaningful it is.

The most effective communication makes ideas explicit. We may take one idea and pit it against another. We may seek the evidence behind an idea or the consequences pursuing it. We might enrich an idea with our feelings about it. Whatever strategy we adopt, our purpose in communicating is to create and share ideas.

Conversation: the heart of communication

Conversation is the main way we communicate. Through conversation we build relationships, share information and promote our ideas. All the other ways we communicate – interviews, presentations, networking meetings, even written documents – are conversations of some kind. Organisations are networks of conversations.

Conversations are the way we create shared meaning. If we want to improve our communication skills, we could begin by improving our conversations.

You May Also Need to Check: