The ability to persuade and influence has never been in more demand among managers. The days of simply telling people what to do and expecting them to do it are long gone. Now you have to be able to ‘sell your ideas’.

The key to effective persuasion is having powerful ideas and delivering them well. Ideas are the currency of communication. Information alone will never influence anyone to act. Only ideas have the power to persuade.

The old word for this power is rhetoric. Since ancient times, the art of rhetoric has taught people how to assemble and deliver their ideas. Few people – at least in Europe – now study rhetoric systematically. Yet, by applying a few simple principles, you can radically improve the quality of your persuasion.

Character, Logic and Passion

Aristotle, the grandfather of rhetoric, claimed that we can persuade in two ways: through the evidence that we can bring to support our case, and through what he called ‘artistic’ persuasion.

Evidence is whatever we can display to support our case. We might use documents or witnesses; these days, we might use the results of research or focus groups.

‘Artistic’ persuasion consists of three appeals using the skills of the persuader themselves:

• appealing to their reason;

• appealing to the audience’s sense of your character or reputation; and

• appealing to their emotions.

Aristotle’s names for these appeals – ethos, logos and pathos – have become well known.

-

Logic (logos)

Logic is the work of rational thought. By using logos, we are appealing to our audience’s ability to reason. We construct an argument, creating reasons to support the case we are making and demonstrating that those reasons logically support the case. Logic comes in two forms: deductive and inductive. (More about logic later in this chapter.)

-

Character (ethos)

Rhetoricians realised very early on that people were swayed as much by passions and prejudices as by reason. For example, we tend to believe people whom we trust or respect. Ethos is the appeal to our audience through personality, reputation or personal credibility. Why should your listener believe what you are telling them? What are your qualifications for saying all this? Where is your experience and expertise? How does your reputation stand with them? What value can you add to the argument from your own experience? Your character creates the trust upon which you can build your argument.

-

Passion (pathos)

In the end, human beings are probably influenced to act more by their emotions than by anything else. Appealing to their feelings – pathos – is thus a vital element in any attempt to persuade.

We tend to think of appealing to emotion as manipulative. Part of our suspicion arises from the fact that this appeal must always be indirect or underhand. We can lay out our argument or our credentials openly, but we cannot announce to our audience that we are about to appeal to their emotions; they will immediately be put on their guard. Neither can we inspire an emotion by talking about it; we must present something external that will arouse emotion. A charitable appeal, for example, might seek to arouse people to donate by showing pictures of children dying in hospital, or animals in distress. Feeling the emotion – or displaying it – may be helpful, but a dispassionate presentation or description will often be more emotionally arousing than an emotional one.

Pathos thus has the reputation of being dishonest or unethical. And we know that speakers can inspire audiences to wildly irrational and dangerous behaviour by playing on their emotions. But the abuse of pathos doesn’t mean we should avoid it. Persuading without emotion is unlikely to be effective, partly because it will seem inhuman (Mr Spock on Star Trek continually had this problem when trying to persuade his colleagues to act rationally).

The aim of pathos must be to arouse the emotional response that is appropriate to the case you are arguing. Emotion need not be overwhelming. If we allow the subject matter or the occasion to elicit emotion in the audience, we shall probably exercise pathos well.

All three of these qualities – character, reasoning and passion – must be present if you want to persuade someone. The process of working out how to persuade them consists of five key elements:

• identifying the core idea;

• arranging your ideas logically;

• developing an appropriate style in the language you use;

• remembering your ideas;

• delivering your ideas with words, visual cues and non-verbal behaviour.

What’s the Big Idea?

If you want to persuade someone, you must have a message. What do you want to say? What’s the big idea? You must know what idea you want to promote. A single governing idea is more likely to persuade your listener than a group of ideas, simply because one strong idea is easier to remember.

Begin by gathering ideas. Conduct imaginary conversations in your head and note down the kind of things you might say. Capture ideas as they occur to you and store them on a pad or in a file. Spend as much time as you can on this activity before the conversation itself.

Having captured and stored some ideas, ask three fundamental questions:

• ‘What is my objective?’ What do I want to achieve? What would I like to see happen?

• ‘Who am I talking to?’ Why am I talking to this person about this objective? What do they already know? What more do they need to know? What do I want them to do? What kind of ideas will be most likely to convince them?

• ‘What is the most important thing I have to say to them?’ If I were only allowed a few minutes with them, what would I say to convince them – or, at least, to persuade them to keep listening?

Think hard about these three questions. Imagine that you had only a few seconds to get your message across. What would you say?

Try to create a single sentence. Remember that you can’t express an idea without uttering a sentence. Above all, this idea should be new to the listener. After all, there’s no point in trying to persuade them of something they already know or agree with!

Once you have decided on your message, consider whether you think it is appropriate both to your objective and to your listener. Does this sentence express what you want to say? Is it in language that the listener will understand easily? Is it simple enough?

Now test your message sentence. If you were to speak this sentence to your listener, would they ask you a question? If so, what would that question be? If your message is a clear one, it will provoke one of these three questions:

• ‘Why?’

• ‘How?’

• ‘Which ones?’

If you can’t imagine your listener asking any of these questions, they’re unlikely to be interested in your message. So try another. If you can imagine them asking more than one of these questions, try to simplify your message.

Now work out how to bring your listener to the place where they will accept this message. You must ‘bring them around to your way of thinking’. This means starting where the listener is standing and gently guiding them to where you want them to be. Once you are standing in the same place, there is a much stronger chance that you will see things the same way. Persuading them will become a great deal easier.

People will only be persuaded by ideas that interest them. Your listener will only be interested in your message because it answers some need or question that already exists in their mind. An essential element in delivering your message, then, is demonstrating that it relates to that need or that question.

Here is a simple four-point structure that will bring your listener to the point where they can accept your message. I remember it by using the letters SPQR.

-

Situation

Briefly tell the listener something they already know. Make a statement about the matter that you know they will agree with. This demonstrates that you are on their territory: you understand their situation and can appreciate their point of view. Try to state the Situation in such a way that the listener expects to hear more. Think of this as a kind of ‘Once upon a time…’. It’s an opener, a scene-setting statement that prepares them for what’s to come.

-

Problem

Now identify a Problem that has arisen within the Situation. The listener may know about the Problem; they may not. But they certainly should know about it! In other words, the Problem should be their problem at least as much as yours.

-

What’s the problem?

• Situation Problem

• Stable, agreed Something’s gone wrong

• status quo Something could go wrong

Something’s changed

Something could change

Something new has arisen

Someone has a different point of view

We don’t know what to do

There are a number of things we could do

Problems, of course, come in many shapes and sizes. It’s important that you identify a Problem that the listener will recognise. It must clearly relate to the Situation that you have set up: it poses a threat to it or creates a challenge within it.

Problems can be positive as well as negative. You may want to alert your listener to an opportunity that has arisen within the Situation.

-

Question

The Problem causes the listener to ask a Question (or would do so, if they were aware of it). Once again, the listener may or may not be asking the Question. If they are, you are better placed to be able to answer it. If they are not, you may have to carefully get them to agree that this Question is worth asking.

-

What’s the question?

| Situation | Problem | Question |

| Stable, Agreed | Agreed Something’s gone | What do we do? |

| Status Quo | Wrong | |

| Something could go wrong | How do we stop it? | |

| Something’s changed | How do we adjust to it? | |

| Something could change | How do we prepare for it? | |

| Something new has arisen | What can we do? | |

| Someone has a different point of view | Who’s right? | |

| We don’t know what to do | What do we do?

or How do we choose? |

|

| There are a number of things we could do | Which course do we take? |

-

Response

Your Response or answer to the Question is your message. In other words, the message should naturally emerge as the logical and powerful answer to the Question raised in the listener’s mind by the Problem!

SPQR is a classic story-telling framework. It is also well known as a method management consultants use in the introductions to their proposals. The trick is to take your listener through the four stages quickly. Don’t be tempted to fill out the story with lots of detail. As you use SPQR, remember these three key points:

1. SPQR should remind the listener rather than persuade them. Until you get to the message, you shouldn’t include any idea that you would need to prove.

2. Think of SPQR as a story. Keep it moving. Keep the listener’s interest.

3. Adapt the stages of the story to the needs of the listener. Make sure that they agree to the first three stages without difficulty. Make sure that you are addressing their needs, values, priorities. Put everything in their terms.

Arranging Your Ideas

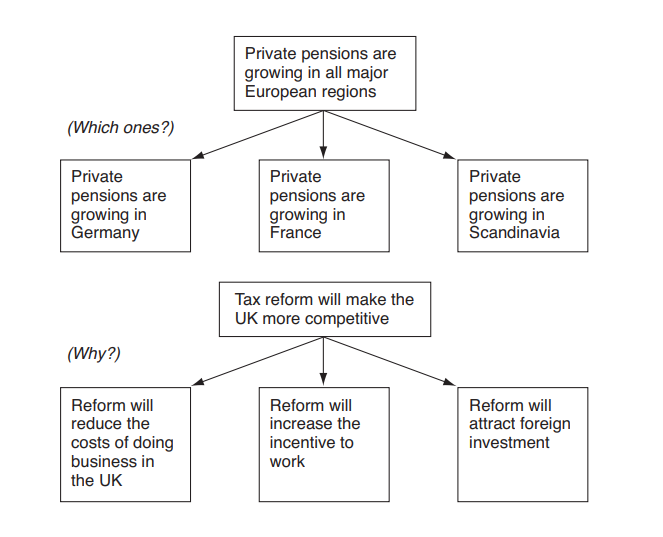

Logic is the method by which you assemble ideas into a coherent structure. So you must have a number of key ideas that support the message you have chosen. Ideally, they are answers to the question you can imagine your listener asking when you utter your message.

-

Finding your key Ideas

| If your message provokes the listener to ask: | Your key ideas will be: |

| ‘Why?’ | Reasons, benefits or causes |

| ‘How?’ | Methods, ways to do something, procedures |

| ‘Which ones?’ | These ones: items in a list |

There are two ways to organise ideas logically. They can be organised deductively, in a sequence, and inductively, in a pyramid.

-

Arguing Deductively

Deductive logic takes the form of a syllogism: an argument in which a conclusion is inferred from two statements

To argue deductively:

• make a statement;

• make a second statement that relates to the first – by commenting on either the subject of the first statement, or on what you have said about that subject;

• state the implication of these two statements being true simultaneously. This conclusion is your message.

-

Arguing Inductively

Inductive logic works by stating a governing idea and then delivering a group of other ideas that the governing idea summarises. Another name for this kind of logic is grouping and summarising.

Inductive logic creates pyramids of ideas. You can test the logic of the structure by asking whether the ideas in any one group are answers to the question that the summarising idea provokes. (You’ve done this already when formulating your message.) That question will be one of three: ‘Why?’, ‘How?’ or ‘Which ones?’

Inductive logic tends to be more powerful in business than deductive logic. Deductive logic brings two major risks with it.

1. It demands real patience on the part of the listener. If you put too many ideas into your sequence, you may stretch their patience to breaking point.

2. You may undermine your own argument. Each stage in the deductive sequence is an invitation to the listener to disagree. And they only have to disagree with one of the stages for the whole sequence to collapse.

Inductive logic avoids both of these perils. First, it doesn’t strain the listener’s patience so much because the main idea – the message – appears at the beginning. Secondly, a pyramid is less likely to collapse than a strung-out sequence of ideas. It’s easier to construct than a deductive sequence because you can see more clearly whether your other ideas support your message. And the message has a good chance of surviving even if one of the supporting ideas is removed. Pyramids of ideas satisfy our thirst for answers now and evidence later. They allow you to be more creative in assembling your ideas and they put the message right at the front.

Deductive logic is only really useful for establishing whether something is true. Inductive logic can also help you to establish whether something is worth doing.

Expressing your Ideas

It’s not enough to have coherent ideas, logically organised. You have to bring the ideas alive in the listener’s mind. You have to use words to create pictures and feelings that will stimulate their senses as well as their brain.

We don’t remember words. We forget nearly everything others say. But we do remember images – particularly images that excite sensory impressions and feelings. If you can excite your listener’s imagination through the senses and stimulate some feeling in them, you will be able to plant the accompanying idea in their long-term memory.

Memory = image + feeling

The word ‘image’, of course, powerfully suggests something visual. But you can create impressions through any of the five senses: sight, hearing, touch, smell and taste. Some people will be convinced by pictures; others will only be persuaded if they hear the words come out of their own mouth. Others again will only remember and learn by touching: they are the ‘hands-on’ people who demand demonstrations and practice.

Neuro-linguistic programming (NLP) works on the basis of people’s natural sensory preferences for receiving information. NLP seeks to develop this awareness of sensory preference into a systematic approach to communicating.

Even without training or study, however, you can become more attuned to the way you respond to ideas with your senses. Whenever you are seeking to persuade someone with an idea, think about how each of the five senses might respond to it. Try to create an impression of the idea that will appeal to one or other of the senses. You’ll find that the idea comes magically alive.

-

Examples

Perhaps the simplest way to bring an idea alive is to offer a concrete example. Find an instance where the idea has been put into practice, or where it has created real results – either useful or disastrous.

Examples can be powerfully and immediately persuasive. Concrete instances and applications of ideas make us take the ideas more seriously. It may be easier to befuddle your listener by talking in abstract terms; but a single clear example will clarify your idea immediately.

-

Stories

Stories are special kinds of examples. They lend weight to the example by making it personal. They also have the benefit of entertaining the listener, keeping them in suspense and releasing an emotional response with a surprising revelation. Much everyday persuasion and explanation is in the form of stories: gossip, jokes, speculation, ‘war stories’ or plain rumour.

Stories work best when they are concrete and personal. Tell your own, authentic stories. They will display your character and your passion. They will also be easier to remember! If you want to tell another person’s story, explain that it’s not yours and tell it swiftly. A story will persuade your listener if it has a clear point. Without a point, it can become counterproductive: an annoying diversion and a waste of time. You may need to make it clear: ‘and the point of the story is…’.

-

Using Metaphors

Using metaphors, as discussed in Chapter 3, is the technique of expressing one thing in terms of another. Metaphors allow you to see things in new ways by showing how they relate to others. The most persuasive metaphors are those that make a direct appeal to the senses and to experience.

Metaphors create meaning. They burn ideas into your listener’s mind (that’s a metaphor!). They help listeners to remember by creating pictures (or sounds, or tastes, or smells) that they can store in their mind (I’m using the metaphor of a cupboard or library to explain some part of the mind’s working).

Remembering your Ideas

Memory played a vital role in the art of rhetoric in the days before printing. With no ready means of making notes or easy access to books, remembering ideas and their relationships was an essential skill. Whole systems of memory were invented to help people store information and recall it at will.

These days, memory hardly seems to figure as a life skill – except for passing examinations. It seems that technology has taken its place. There is no need to remember: merely to read and store e-mails, pick up messages (voice and text) on the mobile, plug in, surf and download…

However, memory still plays an important part in persuading others. If you can’t begin to persuade someone without a heap of spreadsheets and a briefcase full of project designs to refer to, don’t start. Nobody was ever persuaded by watching someone recite from a sheaf of notes.

Find a way to bring the ideas off paper and into your head. Give yourself some clear mental signposts so that you can find your way from one idea to the next. Write a few notes on a card or on the back of your hand. Draw a mindmap. Make it colourful. If you’ve assembled a mental pyramid, draw it on a piece of paper and carry it with you. Have some means available to draw your thoughts as you explain them: a notepad, a flip chart, a whiteboard. Invite the other person to join in: encourage them to think of this as the shape of their thinking.

-

Delivering Effectively

Delivery means supporting your ideas with effective behaviour. Chapter 2 showed how non-verbal communication is a vital component in creating understanding. When you are seeking to persuade, your behaviour will be the most persuasive thing about you. If you are saying one thing but your body is saying another, no one will believe your words.

Think about the style of delivery your listener might prefer. Do they favour a relaxed, informal conversational style or a more formal, presentational delivery? Are they interested in the broad picture or do they want lots of supporting detail? Will they want to ask questions?

Delivery is broadly about three kinds of activity. Think about the way you use your:

• eyes;

• voice;

• body.

-

Effective Eye Contact

People speak more with their eyes than with their voice. Maintain eye contact with your listener. If you are talking to more than one person, include everybody with your eyes. Focus on their eyes: don’t look through them. There are two occasions when you might break eye contact: when you are thinking about what to say next; and when you are looking at notes, a mindmap or some other object of common attention.

-

Using Your Voice

Your voice will sound more persuasive if it is not too high, too fast or too thin. Work to regulate and strengthen your breathing while you speak. Breathe deep and slow. Let your voice emerge more from your body than from your throat. Slow down the pace of your voice, too: it can be all too easy to gabble when you are involved in an argument or nervous about the other person’s reactions. The more body your voice has, and the more measured your vocal delivery, the more convincing you will sound.

-

Persuasive Body Language

Your face, your limbs and your body posture will all contribute to the total effect your ideas have on the listener. To start with, try not to frown. Keep your facial muscles moving and pay attention to keeping your neck muscles relaxed. Use your hands to paint pictures, to help you find the right words and express yourself fully.

Professional persuaders observe their listeners’ behaviour and quietly mirror it. If you are relaxed with the other person, such mirroring will tend to happen naturally: you may find you are crossing your legs in similar ways or moving your arms in roughly the same way. Try consciously to adapt your own posture and movement to that of the person listening to you. Do more: take the lead. Don’t sit back or close your body off when you are seeking to persuade; bring yourself forward, open yourself up and present yourself along with your ideas.

You May Also Need to Check: