The skills of enquiry are the skills of listening. And the quality of your conversation depends on the quality of your listening. Only by enquiring into the other person’s ideas can you respond honestly and fully to them. Only by discovering the mental models and beliefs that underlie those ideas can you explore the landscape of their thinking. Only by finding out how they think can you begin to persuade them to your way of thinking.

Skilled enquiry actually helps the other person to think better. Listening – real, deep, attentive listening – can liberate their thinking.

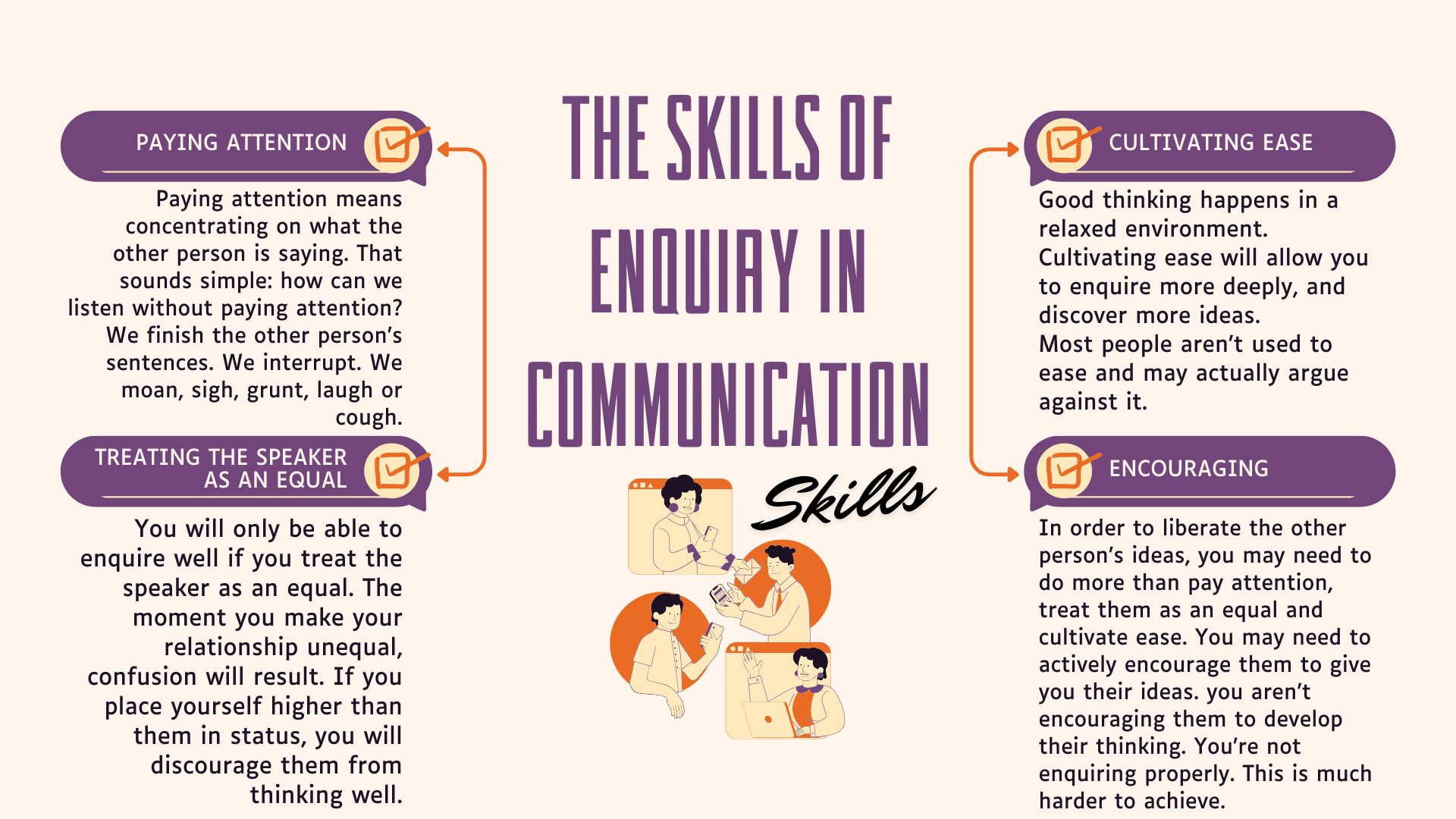

I’ve summarised the skills of enquiry under seven headings:

- Paying Attention

- Treating the Speaker as an Equal

- Cultivating Ease

- Encouraging

- Asking Quality Questions

- Rationing Information

- Giving positive Feedback

Acquiring these skills will help you to give the other person the respect and space they deserve to develop their own ideas – to make their thinking visible.

1. Paying Attention

Paying attention means concentrating on what the other person is saying. That sounds simple: how can we listen without paying attention?

Of course, this is what happens most of the time. We think we’re listening, but we aren’t. We finish the other person’s sentences. We interrupt. We moan, sigh, grunt, laugh or cough.

We fill pauses with our own thoughts, stories or theories. We look at our watch or around the room. We think about the next meeting, or the next report, or the next meal. We frown, tap our fingers, destroy paperclips and glance at our diary. We give advice. We give more advice.

We think our own thoughts when we should be silencing them. Real listening means shutting down our own thinking and allowing the other person’s thinking to enter.

A lot of what we hear when we listen to another person is our effect on them. If we are paying proper attention, they will become more intelligent and articulate. Poor attention will make them hesitate, stumble and doubt the soundness of their thinking. Poor attention makes people more stupid.

I think that, deep down, we have two mental models about listening. We hold them so deeply that we’re hardly aware of them. And they do more to damage the quality of our listening than anything else.

The first mental model is that people listen in order to work out a reply. This seems a reasonable enough idea. But it’s wrong. If people listen so that they can work out what they should think, then they aren’t listening closely enough to what the other person thinks. They are not paying attention.

The second mental model is that people reply in order to tell the other person what to think. In fact, this model implies that people will talk to us only because they want our ideas. This model, too, is wrong.

Listening well means helping the other person to find out their ideas. The mind containing the problem probably also contains the solution. Their solution is likely to be much better than ours because it’s theirs. Paying attention means helping the other person to make their thinking visible.

Of course, the other person may actually want advice. But don’t assume that this is the case. Wait for them to ask; if necessary, ask them what they want from you. Don’t rush. Give them the chance to find their own ideas first. Paying attention in this way will probably slow the conversation down more than you feel is comfortable. Adjust your own tempo to that of the other person. Wait longer than you want to.

Listen. Listen. And then listen some more. And when they can’t think of anything else to say, ask: ‘What else do you think about this? What else can you think of? What else comes to mind?’ That invitation to talk more can bring even the weariest brain back to life.

-

Interrupting

Interrupting is the most obvious symptom of poor attention. It’s irresistible. Some demon inside us seems to compel us to fill the other person’s pauses with words. It’s as if the very idea of silence is terrifying.

Mostly people interrupt because they are making assumptions. Here are a few. Next time you interrupt someone in a conversation, ask yourself which of them you are applying.

- My idea is better than theirs.

- The answer is more important than the problem.

- I have to utter my idea fast and if I don’t interrupt, I’ll lose my chance (or forget it).

- I know what they’re going to say.

- They don’t need to finish the sentence because my rewrite is an improvement.

- They can’t improve this idea any further, so I might as well improve it for them.

- I’m more important than they are.

- It’s more important for me to be seen to have a good idea than for me to let them finish.

- Interrupting will save time.

Put like that, these assumptions are shown up for what they are: presumptuous, arrogant, silly. You’re usually wrong when you assume that you know what the other person is about to say. If you allow them to continue, they will often come up with something more interesting, more colourful and more personal.

-

Allowing Quiet

Once you stop interrupting, the conversation will become quieter. Pauses will appear. The other person will stop talking and you won’t fill the silence.

These pauses are like junctions. The conversation has come to a crossroads. You have a number of choices about where you might go next. Either of you might make that choice. If you are interested in persuading, you will seize the opportunity and make the choice yourself. But, if you are enquiring, then you give the speaker the privilege of making the choice.

There are two kinds of pause. One is a filled pause; the other is empty. Learn to distinguish between the two.

Some pauses are filled with thought. Sometimes, the speaker will stop. They will go quiet, perhaps suddenly. They will look elsewhere, probably into a longer distance. They are busy on an excursion. You’re not invited. But they will want you to be there at the crossroads when they come back. You are privileged that they have trusted you to wait. So wait.

The other kind of pause is an empty one. Nothing much is happening. The speaker doesn’t stop suddenly; instead, they seem to fade away. You are standing at the crossroads in the conversation together, and neither of you is moving. The energy seems to drop out of the conversation. The speaker’s eyes don’t focus anywhere. If they are comfortable in your company, they may focus on you as a cue for you to choose what move to make.

Wait out the pause. If the pause is empty, the speaker will probably say so in a few moments. ‘I can’t think of anything else.’ ‘That’s it, really.’ ‘So. There we are. I’m stuck now.’ Try asking that question: ‘Can you think of anything else?’ Resist the temptation to move the conversation on by asking a more specific question. The moment you do that, you have closed down every other possible journey that you might take together: you are dictating the road to travel. Make sure that you only do so once the other person is ready to let you take the lead.

-

Showing that You are Paying Attention

Your face will show the other person whether you are paying attention to them. In particular, your eyes will speak volumes about the quality of your listening.

-

How to show that You are Paying Attention

Pay attention! If you actually pay attention, you will look as if you are paying attention.

Relax your facial muscles. Try not to frown. No rigid smiles.

Keep your eyes on the person doing the talking. If you take your eyes away from them, be ready to bring your gaze back to them soon. (The speaker will probably look away frequently: that’s what we do when we’re thinking.)

Think about the angle at which you are sitting or standing. Sixty degrees gives eyes a useful escape lane.

Use minimal encouragers. (For more, look below under ‘Encouraging’.)

Make notes. If necessary, ask them to pause while you make your note.

By behaving as if you are interested, you can sometimes become more interested. It may be that such attentive looking actually inhibits the speaker. In some cultures, looking equates to staring and is a sign of disrespect. You need to be sensitive to these possible individual or cultural distinctions and adapt your eye movements accordingly. Generally, people do not look nearly enough at those they are listening to. The person speaking will pick up the quality of your attention through your eyes – possibly unconsciously – and the quality of their thinking will improve as a result.

2. Treating the Speaker as an Equal

You will only be able to enquire well if you treat the speaker as an equal. The moment you make your relationship unequal, confusion will result. If you place yourself higher than them in status, you will discourage them from thinking well. If you place them higher than you, you will start to allow your own inhibitions to disrupt your attention to what they are saying.

Patronising the speaker is the greatest enemy of equality in conversations. This conversational sin derives from the way people are treated as children – and the way some people subsequently treat children. Sometimes children have to be treated like children. It is necessary to:

- Decide for them

- Direct them

- Tell them what to do

- Assume that adults know better than they do

- Worry about them

- Take care of them

- Control them

- Think for them

There is a tendency to carry this patronising behaviour over into conversations with other adults. As soon as you think you know better than the other person, or provide the answers for them, or suggest that their thinking is inadequate, you are patronising them. You can’t patronise somebody and pay them close attention at the same time.

Treat the other person as an equal and you won’t be able to patronise them. If you don’t value somebody’s ideas, don’t hold conversations with them. But if you want ideas that are better than your own, if you want better outcomes and improved working relationships, work hard on giving other people the respect that they and their ideas deserve.

3. Cultivating Ease

Good thinking happens in a relaxed environment. Cultivating ease will allow you to enquire more deeply, and discover more ideas.

Most people aren’t used to ease and may actually argue against it. They’re so used to urgency that they can’t imagine working in any other way. Many organisations actually dispel ease from the workplace. Ease is equated with sloth. If you’re not working flat out, chased by deadlines and juggling 50 assignments at the same time, you’re not worth your salary. It’s assumed that the best thinking happens in such a climate.

This is wrong. Urgency keeps people from thinking well. They’re too busy doing. After all, doing is what gets results, isn’t it? Not when people have to think to get them. Sometimes, the best results only appear by not doing: by paying attention to someone else’s ideas with a mind that is alert, comfortable, and at ease. When you are at ease, the solution to a problem will appear as if by magic.

-

How to Cultivate Ease

Find the time. If the situation is urgent, postpone the conversation.

Make space. A quiet space; a neutral space; a comfortable space.

Banish distractions. Unplug the phones. Leave the building. Barricade the door.

Cultivating ease in a conversation is largely a behavioural skill. Make yourself comfortable. Lean back, breathe out, smile, look keen, and slow down your speaking rhythm.

4. Encouraging

In order to liberate the other person’s ideas, you may need to do more than pay attention, treat them as an equal and cultivate ease. You may need to actively encourage them to give you their ideas.

Remember that the other person’s thinking is to a large extent the result of the effect you have on them. So if you:

• Suggest that they change the subject;

• Try to convince them of your point of view before listening to their point of view;

• Reply tit-for-tat to their remarks; or

• Encourage them to compete with you,

– you aren’t encouraging them to develop their thinking. You’re not enquiring properly.

Competitiveness is one of the worst enemies of encouragement. It’s easy to slip into a ritual of using the speaker’s ideas to promote your own. It’s all part of the tradition of adversarial thinking that is so highly valued in Western society.

If the speaker feels that you are competing with them in the conversation, they will limit not only what they say but also what they think. Competition forces people to think only those thoughts that will help them win. Similarly, if you feel that the speaker is trying to compete with you, don’t allow yourself to enter the competition. This is much harder to achieve. The Ladder of Inference (see Chapter 3) is one very powerful tool that will help you to defuse competitiveness in your conversations.

Instead of competing, welcome the difference in your points of view. Encourage a positive acknowledgement that you see things differently and that you must deal with that difference if the conversation is to move forward.

-

Minimal Encouragers

Minimal encouragers are brief, supportive statements and actions that convey attention and understanding.

They can be:

• sub-vocalisations: ‘uh-huh’, ‘mm’;

• words and phrases: ‘right’, ‘really?’, ‘I see’;

• repeating key words.

Behaviours can include:

• leaning forward;

• focusing eye contact;

• head-nodding.

Benefits:

• can support the speaker without interrupting them;

• demonstrate your interest;

• encourage the speaker to continue;

• show appreciation of particular points: successes, ideas the speaker finds important;

• indicate recognition of emotion or deep feeling.

Potential problems:

• can be used to direct the course of the conversation: a subtle form of influence;

• can reinforce the speaker’s behaviour in a particular direction: they may start to say things in the hope of receiving the ‘prize’ of a minimal encourager;

• if unsynchronised with other behaviours, may indicate impatience or a desire to move on;

• can become a ritualised habit, empty of meaning.

5. Asking Quality Questions

Questions are the most obvious way to enquire into other people’s thinking. Yet it’s astonishing how rarely managers ask quality questions.

Questions, of course, can be loaded with assumptions. They can be politically charged. In some conversations, the most important questions are never asked because to do so would be to challenge the centre of authority. To ask a question can sometimes seem like revealing an unacceptable ignorance. In some organisations, to ask them is simply ‘not done’.

‘Questioning,’ said Samuel Johnson on one occasion, ‘is not the mode of conversation among gentlemen.’

Questions can also be used in ways that don’t promote enquiry. Specifically, managers sometimes use questions to:

• emphasise the difference between their ideas and other people’s;

• ridicule or make the other person look foolish;

• criticise in disguise;

• find fault;

• make themselves look clever;

• express a point of view in code;

• force the other person into a corner;

• create an argument.

The only legitimate use of a question is to foster enquiry. Questions help you to:

• find out facts;

• check your understanding;

• help the other person to improve their understanding;

• invite the other person to examine your own thinking;

• request action.

The best questions open up the other person’s thinking. A question that helps the other person think further, develop an idea or make their thoughts more visible to you both, is a highquality question.

A whole repertoire of questions is available to help you enquire more fully. Specifically, we can use six types of questions:

• Closed questions. Can only be answered ‘yes’ or ‘no’.

• Leading questions. Put the answer into the other person’s mouth.

• Controlling questions. Help you to take the lead in the conversation.

• Probing questions. Build on an earlier question, or dig deeper.

• Open questions. Cannot be answered ‘yes’ or ‘no’.

• Reflecting questions. Restate the last remark with no new request.

This powerful tool can provide questions that allow you to enquire into the speaker’s thinking. You can also use it to invite them to enquire into yours.

The highest quality questions actually liberate the other person’s thinking. They remove the assumptions that block thinking and replace them with other assumptions that set it free. The key is identifying the assumption that might be limiting the other person’s thinking. You don’t have to guess aright: asking the question may tell you whether you’ve identified it correctly; if it doesn’t, it may well open up the speaker’s thinking anyway.

These high quality questions are broadly ‘What if’ questions. You can either ask a question in the form ‘What if this assumption weren’t true?’ or in the form ‘What if the opposite assumption were true?’

Examples of the first kind of question might include:

• What if you became chief executive tomorrow?

• What if I weren’t your manager?

• What if you weren’t limited in your use of equipment?

Examples of the second kind might include:

• What if you weren’t limited by a budget?

• What if customers were actually flocking to us?

• What if you knew that you were vital to the company’s success?

People are often inhibited from developing their thinking by two deep assumptions. One is that they are incapable of thinking well about something, or achieving something. The other is that they don’t deserve to think well or achieve. Asking good questions can help you to encourage the other person to overcome these inhibitors and grow as a competent thinker.

6. Rationing Information

Information is power. Sometimes, as part of enquiry, you can supply information that will empower the speaker to think better. Withholding information is an abuse of your power over them.

The difficulty is that giving information disrupts the dynamic of listening and enquiring. A few simple guidelines will help you to ration the information that you supply.

• Don’t interrupt. Let the speaker finish before giving any new information. Don’t force information into the middle of their sentence.

• Time your intervention. Ask yourself when the most appropriate time might be to offer the information.

• Filter the information. Only offer information that you think will improve the speaker’s thinking. Resist the temptation to amplify some piece of information that is not central to the direction of their thinking.

• Don’t give information to show off. You may be tempted to give information to demonstrate how expert or up to date you are. Resist that temptation.

Asking the speaker for information is also something you should ration carefully. You need to make that request at the right time, and for the right reason. To ask for it at the wrong time may close down their thinking and deny you a whole area of valuable ideas.

Following this advice may mean that you have to listen without fully understanding what the speaker is saying. You may even completely misunderstand for a while. Remember that enquiry is about helping the other person clarify their thinking. If asking for information will help only you – and not the speaker – you should consider delaying your request. In enquiry, it’s more important to let the speaker do their thinking than to understand fully what they are saying. This may seem strange, but if you let the speaker work out their thinking rather than keeping you fully informed, they will probably be better able to summarise their ideas clearly to you when they’ve finished.

7. Giving Positive Feedback

Feedback is the way we check that our enquiry has been successful. But feedback can do more. It can prepare us to switch the mode of conversation from enquiry to persuasion. It can also help us to end a conversation; summarising your response to what the speaker has said and providing the foundations for a conversation for action.

There are two kinds of feedback: positive and negative. It’s obvious in simple terms how they differ. Positive feedback is saying that we like, appreciate and value the speaker’s ideas. Negative feedback is saying that we dislike them, are hostile to them or place no value on them.

Clearly the two kinds of feedback have wider implications. Positive feedback encourages the other person to go on thinking. Negative feedback is likely to stop them thinking at all. Positive feedback also encourages the speaker to value their own thinking; negative feedback tells them that their thinking is worthless. Positive feedback makes people more intelligent. Negative feedback makes them more stupid.

Negative feedback is usually a sign that we are adopting what one consultant calls ‘Negative reality norm theory’. This is the theory that only negative attitudes are realistic. We see this theory at work every day in our newspapers. News, almost by definition, is bad news. The phrase ‘good news’ is virtually a contradiction in terms.

We live out the theory in our everyday lives and in our conversations. To be positive is to be naive and simplistic; it makes us vulnerable. To be negative is to be well informed and protected from the ‘slings and arrows of outrageous fortune’. Whenever we say ‘we must be realistic’, we usually mean that we should emphasise the negative aspects of the situation.

Given this social norm, to be positive can seem like challenging reality, or importing some new and alien idea into our picture of it. Actually, of course, the positive is merely another part of our picture of reality. In adding it to the negative, we are completing the picture, not distorting it.

The best kind of feedback is genuine, succinct and specific. If you fake it, they will rumble you. If you go on, they will suspect your honesty. If you are too general, they will find it hard to make use of the feedback.

-

Balancing Appreciation and Criticism

We tend to think of feedback as a one-off activity. Actually, we are feeding back to the speaker all the time we are listening to them. Be sure that the continuous feedback you give indicates your respect for them, as people and as thinkers, even if you disagree with their ideas.

Make sure that your positive feedback outweighs the negative. A good working ratio might be five-to-one: five positive remarks for every negative one. This can sometimes be difficult to achieve! The speaker may not have delivered any very good ideas. It’s more likely that you can only see what’s bad, or wrong, or incomplete, or inaccurate, about their ideas. Years of training and experience in critical thinking may have taught you not to comment on what you approve or like.

Look for things to be positive about. I think that this is a basic managerial skill, as well as a conversational one. Praise – genuine, succinct and specific – does more to help you manage than any other activity, because it helps people to think and work better than any other motivator.

Get into the habit of asking: ‘What’s good about what this person is saying?’ Force yourself, if necessary, to find some answers to that question; then be sure to give those answers to the speaker. It’s easier to ask this question if you adopt a policy of assuming constructive intent. You might be assuming that the speaker is not trying to do their best thinking, or seeking a genuine solution. In fact, they are likely to be trying to think as well as they can. Assume that they are trying to be positive, and give appropriate feedback. One result, among others, is that the speaker will be encouraged to be more constructive.

The more formal the conversation, the more likely that your feedback will be a single, lengthy contribution. You need to choose carefully when to give your feedback. Too early, and you may close the conversation down prematurely. Too late, and the effect may be lost. If in doubt, you can ask whether it’s appropriate to start your feedback or whether the speaker wants to continue. Ask:

• for permission to feedback;

• how the speaker sees the situation in summary;

• what the speaker sees as the key issue or problem.

Only then should you launch into your own feedback. Give your positive feedback before any negative feedback

Make your own objective clear and explain how your feedback relates to that objective. Feedback will naturally become more positive if you make it forward-looking: what you and the other person are trying to achieve, what you both want to do. The best negative feedback is about whatever is hindering progress towards the objective. You can productively ignore any other ideas that you happen to disagree with.

Feed back on ideas and information, rather than on the person. Support any comments you make with evidence. Focus on the key idea or aspect that you think would change the situation most strongly for the better. If you praise them, the speaker is more likely to accept the need to change their views or their behaviour.

You May Also Need to Check: