Every manager holds interviews. To be able to hold a structured interview with someone to achieve a clear goal is a fundamental managerial skill.

When is an interview not an interview?

The word ‘interview’ simply means ‘looking between us’: an interview is an exchange of views. Any conversation – conducted well – is such an exchange. Interviews differ from other conversations in that they:

• are held for a very specific reason;

• aim at a particular outcome;

• are more carefully and consciously structured;

• must usually cover predetermined matters of concern;

• are called and led by one person – the interviewer;

• are usually recorded.

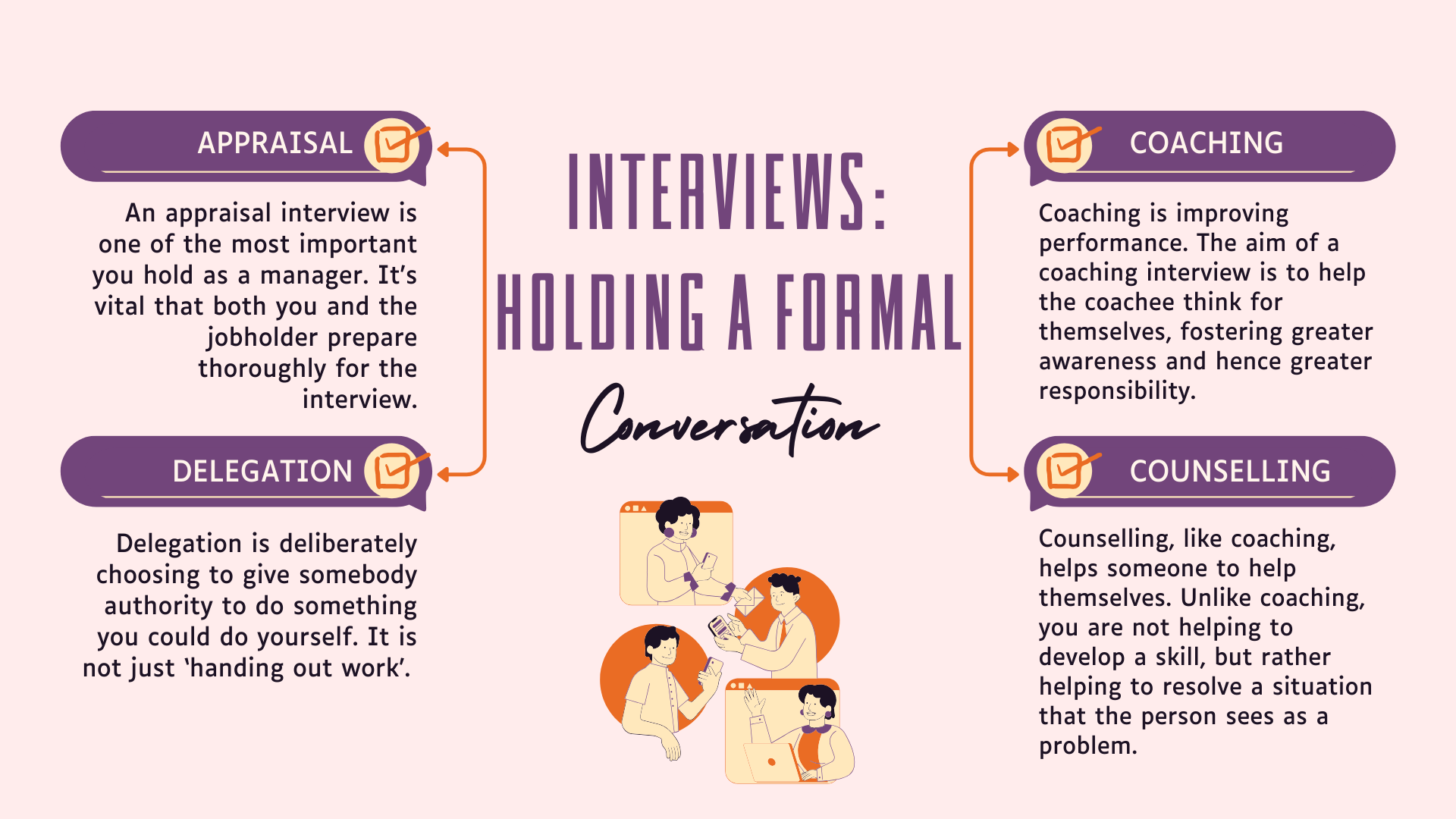

This chapter will look at the following four types of interview:

• Appraisal

• Delegation

• Coaching

• Counselling

Each type of interview will demand a range of skills from you, the interviewer. All of the skills of enquiry and persuasion that have been explored so far in this book will come into play at some point.

Preparing for the interview

Prepare for the interview by considering three questions:

• What’s my objective?

• What do I need?

• When and where?

-

What’s my objective?

What do you want to achieve in the interview? You must decide, for you are calling the interview. Do you want to discipline a member of staff for risking an accident, or influence their attitude to safety? Are you trying to offload a boring routine task or seeking to delegate as a way of developing a member of your team? Are you counselling or coaching?

Setting a clear objective is the only way you will be able to measure the interview’s success. And it is essential if you want to be able to decide on the style and structure of the interview.

-

What do I need?

Think about the information you will need before and during the interview. Think also about what information the interviewee will need. What are the key areas you need to cover? In what order? What questions do you need to ask?

You may also need other kinds of equipment to help you: notepads, flip charts, files, samples of material or machinery. You may even need a witness to ensure that the interview is seen to be conducted professionally and fairly.

-

When and where?

When do you propose to interview? For how long? The time of day is as important as the day you choose. Certain times of day are notoriously difficult for interview: after lunch, for example – or during lunch! Remember also that an interview that goes on too long will become counterproductive.

The quality of the interview will be strongly influenced by its venue. You may decide that your office is too formal or intimidating; on the other hand, interviewing in a crowded public area or in the pub can destroy the sense of privacy that any interview should encourage. You may decide to conduct some parts of an interview in different places.

Think also about the climate you set up for the interviewee. Sitting them on a low chair, beyond a desk, facing a sunny window, with nowhere to put a cup of coffee, will obviously set up an unpleasant atmosphere.

Structuring the Interview

Interviews, like other conversations, naturally fall into a structure. Interviewers sometimes try to press an interview forward towards a result without allowing enough time for the early stages.

Every interview can be structured using the WASP structure that was examined in Chapter 3. This structure reinforces the fact that both stages of thinking are important.

• Welcome (first-stage thinking). At the start of the interview, state your objective, set the scene and establish your relationship. ‘Why are we talking about this matter? Why us?’ Do whatever you can to help the interviewee relax. Make sure the interviewee understands the rules you are establishing, and agrees to them.

• Acquire (first-stage thinking). The second step is information gathering. Concentrate on finding out as much as possible about the matter, as the interviewee sees it. Your task is to listen. Ask questions only to keep the interview on course or to encourage the interviewee further down a useful road. Take care not to judge or imply that you are making any decision.

• Supply (second-stage thinking). Now, at the third step, the interview has moved on from information gathering to joint problem solving. Review options for action. It’s important at this stage of the interview to remind yourselves of the objective that you set at the start.

• Part (second-stage thinking). Finally, make a decision. You and the interviewee work out what you have agreed. State explicitly the interview’s outcome: the action that will result from it. The essence of the parting stage is that you explicitly agree what is going to happen next. What is going to happen? Who will do it? Is there a deadline? Who is going to check on progress?

What about after the interview? In many cases, you may need time to put your thoughts in order and make decisions. Indeed, it might be entirely inappropriate to decide – or to tell the interviewee what you have decided – at the end of the interview itself. The interviewee, too, may need time to reflect on the interview. Nevertheless, you must tell the interviewee what you expect the next step to be and make sure that they agree to it.