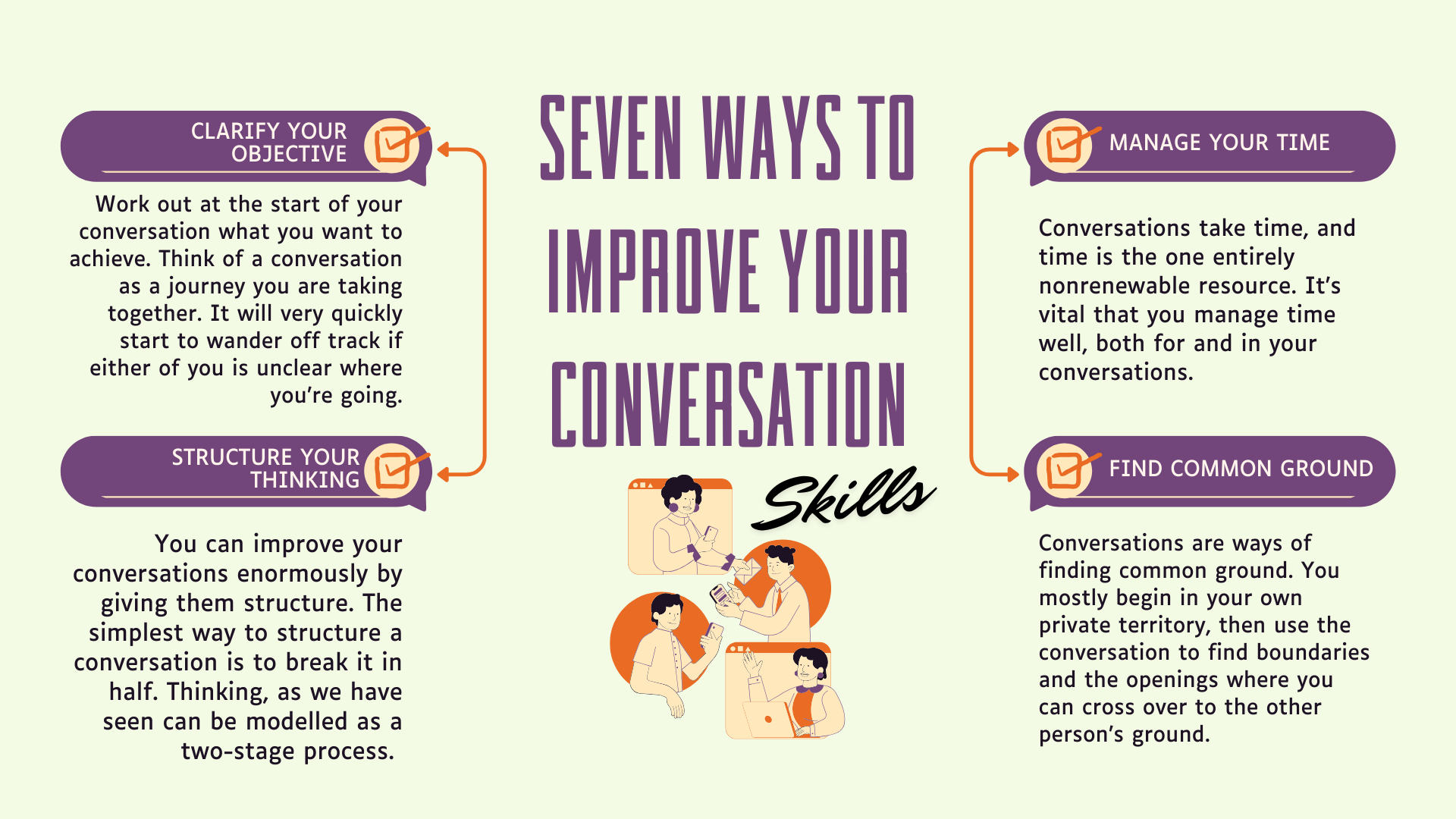

Your success as a manager depends on your ability to hold effective and productive conversations. This chapter looks at seven proven strategies to help you improve your conversations.

- Clarify your objective.

- Structure your thinking.

- Manage your time.

- Find common ground.

- Move beyond argument.

- Summarise often.

- Use visuals.

Don’t feel that you must apply all seven at once. Take a single strategy and work at it for a few days. (You should have plenty of conversations to practise on!) Once you feel that you have integrated that skill into your conversations, move on to another.

1. Clarify your Objective

Work out at the start of your conversation what you want to achieve. Think of a conversation as a journey you are taking together. It will very quickly start to wander off track if either of you is unclear where you’re going. You will complete the journey effectively only if you both know clearly where you are aiming for.

What’s vital is that you state your objective clearly at the start. Give a headline. If you know what your main point is, state it at the start of the conversation.

Of course, you might decide to change your objective in the middle of the conversation – just as you might decide to change direction in the middle of a journey. That’s fine, so long as both of you know what you’re doing. Too specific an objective at the start might limit your success at the end. This problem is at the heart of negotiation, for example: what would you be willing to settle for, and what is not negotiable?

Objectives roughly divide into two categories:

- Exploring a Problem

- Finding a Solution

When you are thinking about your headline, ask ‘problem or solution?’ You may tend to assume that any conversation about a problem is aiming to find a solution – particularly if the other person has started the conversation. As a result, you may find yourself working towards a solution without accurately defining or understanding the problem. It may be that the other person doesn’t want you to offer a solution, but rather to talk through the problem with them.

2. Structure your Thinking

You can improve your conversations enormously by giving them structure. The simplest way to structure a conversation is to break it in half.

Thinking, as we have seen can be modelled as a two-stage process. First-stage thinking is thinking about a problem; secondstage thinking is thinking about a solution.

Many managerial conversations leap to second-stage thinking without spending nearly enough time in the first stage. They look for solutions and almost ignore the problem.

Why this urge to ignore the problem? Perhaps because problems are frightening. To stay with a problem – to explore it, to try to understand it further, to confront it and live with it for a few moments – is too uncomfortable. People don’t like living with unresolved problems. Better to deal with it: sort it out; solve it; get rid of it.

Resist the temptation to rush into second-stage thinking. Give the first stage – the problem stage – as much attention and time as you think appropriate. Then give it a little more. And make sure that you are both in the same stage of the conversation at the same time.

Link the stages of your conversation together. Linking helps you to steer the conversation comfortably. Skilled conversation holders can steer the conversation by linking the following:

- The past and the present

- The problem and the solution

- First-stage and Second-stage thinking

- Requests and answers

- Negative ideas and positive ideas

- Opinions about what is true, with speculation about the consequences

WASP: welcome; acquire; supply; part

In my early days as a manager, I was introduced to a simple four-stage model of conversation that I still use. It breaks down the two stages of thinking into four steps:

- Welcome (first-stage thinking). At the start of the conversation, state your objectives, set the scene and establish your relationship: ‘Why are we talking about this matter? Why us?’

- Acquire (first-stage thinking). The second step is information gathering. Concentrate on finding out as much as possible about the matter, from as many angles as you can. For both of you, listening is vital. You are acquiring knowledge from each other. This part of the conversation should be dominated by questions.

- Supply (second-stage thinking). Now, at the third step, we summarise what we’ve learnt and begin to work out what to do with the information. We are beginning to think about how we might move forward: the options that present themselves. It’s important at this stage of the conversation to remind yourselves of the objective that you set at the start.

- Part (second-stage thinking). Finally, you work out what you have agreed. You state explicitly the conversation’s outcome: the action that will result from it. The essence of the parting stage is that you explicitly agree what is going to happen next. What is going to happen? Who will do it? Is there a deadline? Who is going to check on progress?

From impromptu conversations in the corridor to formal interviews, WASP gives you a simple framework to make sure that the conversation stays on track and results in a practical outcome.

Four Types of Conversation

This simple four-stage model can become more sophisticated. In this developed model, you hold four conversations, for:

- Relationship

- Possibility

- Opportunity

- Action

These four conversations may form part of a single, larger conversation; they may also take place separately, at different stages of a process or project.

A conversation for relationship (‘welcome’)

You hold a conversation for relationship to create or develop the relationship you need to achieve your objective. It is an exploration.

Conversations for relationship are tentative and sometimes awkward. They are often rushed because they can be embarrassing. Think of those tricky conversations you have had with strangers at parties: they are good examples of conversations for relationship. A managerial conversation for relationship should move beyond the ‘What do you do? Where do you live?’ questions. You are defining your relationship to each other, and to the matter in hand.

A conversation for possibility (‘acquire’)

A conversation for possibility continues the exploration: it develops first-stage thinking. It asks what you might be looking at.

A conversation for possibility is not about whether to do something, or what to do. It seeks to find new ways of looking at the problem.

There are a number of ways of doing this.

- Look at it from a new angle.

- Ask for different interpretations of what’s happening.

- Try to distinguish what you’re looking at from what you think about it.

- Ask how other people might see it.

- Break the problem into parts.

- Isolate one part of the problem and look at it in detail.

- Connect the problem into a wider network of ideas.

- Ask what the problem is like. What does it look like, or feel like?

Conversations for possibility are potentially a source of creativity: brainstorming is a good example. But they can also be uncomfortable: exploring different points of view may create conflict.

Manage this conversation with care. Make it clear that this is not decision time. Encourage the other person to give you ideas. Take care not to judge or criticise. Do challenge or probe what the other person says. In particular, manage the emotional content of this conversation with care. Acknowledge people’s feelings and look for the evidence that supports them.

A conversation for opportunity (‘supply’)

A conversation for opportunity takes us into second-stage thinking. This is fundamentally a conversation about planning. Many good ideas never become reality because people don’t map out paths of opportunity. A conversation for opportunity is designed to construct such a path. You are choosing what to do. You assess what you would need to make action possible: resources, support and skills. This conversation is more focused than a conversation for possibility: in choosing from among a number of possibilities, you are finding a sense of common purpose.

The bridge from possibility to opportunity is measurement. This is where you begin to set targets, milestones, obstacles, measures of success. How will you be able to judge when you have achieved an objective?

Recall your original objective. Has it changed? Conversations for opportunity can become more exciting by placing yourselves in a future where you have achieved your objective. What does such a future look and feel like? What is happening in this future? How can you plan your way towards it? Most people plan by starting from where they are and extrapolate current actions towards a desired objective. By ‘backward planning’ from an imagined future, you can find new opportunities for action.

A conversation for action (‘part’)

This is where you agree what to do, who will do it and when it will happen. Translating opportunity into action needs more than agreement; you need to generate a promise, a commitment to act.

Managers often remark that getting action is one of the hardest aspects of managing people. ‘Have you noticed’, one senior director said to me recently, ‘how people seem never to do what they’ve agreed to do?’ Following up on agreed actions can become a major time-waster. A conversation for action is the first step in solving this problem. It’s vital that the promise resulting from a conversation for action is recorded.

This four-stage model of conversation – either in its simple WASP form, or in the more sophisticated form of relationship–possibility–opportunity–action – will serve you well in the wide range of conversations you will hold as a manager. Some of your conversations will include all four stages; some will concentrate on one more than another.

These conversations will only be truly effective if you hold them in order. The success of each conversation depends on the success of the conversation before it. If you fail to resolve a conversation, it will continue underneath the next in code. Unresolved aspects of a conversation for relationship, for instance, can become conflicts of possibility, hidden agendas or ‘personality clashes’. Possibilities left unexplored become lost opportunities. And promises to act that have no real commitment behind them will create problems later.

You May Also Need to Check:

3. Manage your Time

Conversations take time, and time is the one entirely nonrenewable resource. It’s vital that you manage time well, both for and in your conversations.

Managing time for the conversation

Work out how much time you have. Don’t just assume that there is no time. Be realistic. If necessary, make an appointment at another time to hold the conversation. Make sure it’s a time that both of you find convenient.

Managing time in the conversation

Most conversations proceed at a varying rate. Generally, an effective conversation will probably start quite slowly and get faster as it goes on. But there are no real rules about this.

You know that a conversation is going too fast when people interrupt each other a lot, when parallel conversations start, when people stop listening to each other and when people start to show signs of becoming uncomfortable.

Conversely, you know that a conversation is slowing down when one person starts to dominate the conversation, when questions dry up, when people pause a lot, when the energy level in the conversation starts to drop or when people show signs of weariness.

Try to become aware of how fast the conversation is proceeding, and how fast you think it should be going. Here are some simple tactics to help you regain control of time in your conversations.

Speeding up is probably a more common cause of conversation failure than slowing down. Try to slow the conversation down consciously and give first-stage thinking a reasonable amount of time to happen.

4. Find Common Ground

Conversations are ways of finding common ground. You mostly begin in your own private territory, then use the conversation to find boundaries and the openings where you can cross over to the other person’s ground.

Notice how you ask for, and give, permission for these moves to happen. If you are asking permission to move into new territory, you might:

- Make a remark tentatively

- Express yourself with lots of hesitant padding: ‘perhaps we might…’, ‘I suppose I think…’, ‘It’s possible that…’

- Pause before speaking

- Look away or down a lot

- Explicitly ask permission: ‘Do you mind if I mention…?’ ‘May I speak freely about…?’.

You do not proceed until the other person has given their permission. Such permission may be explicit: ‘Please say what you like’; ‘I would really welcome your honest opinion’; ‘I don’t mind you talking about that’. Other signs of permission might be in the person’s body language or behaviour: nodding, smiling, leaning forward.

Conversely, refusing permission can be explicit – ‘I’d rather we didn’t talk about this’ – or in code. The person may evade your question, wrap up an answer in clouds of mystification or reply with another question. Their non-verbal behaviour is more likely to give you a hint of their real feelings: folding their arms, sitting back in the chair, becoming restless, evading eye contact.

5. Move Beyond Argument

One of the most effective ways of improving your conversations is to develop them beyond argument. Most people are better at talking than at listening. At school, we often learn the skills of debate: of taking a position, holding it, defending it, convincing others of its worth and attacking any position that threatens it.

As a result, conversations have a habit of becoming adversarial. Instead of searching out the common ground, people hold their own corner and treat every move by the other person as an attack. Adversarial conversations set up a boxing match between competing opinions.

Opinions are ideas gone cold. They are assumptions about what should be true, rather than conclusions about what is true in specific circumstances. Opinions might include:

- Stories (about what happened, what may have happened, why it happened)Explanations (of why something went wrong, why it failed)

- Justifications for doing what was done

- Gossip (perhaps to make someone feel better at the expense of others)

- Generalisations (to save the bother of thinking)

- Wrong-making (to establish power over the other person).

Opinions are often mistaken for the truth. Whenever you hear someone – maybe yourself – saying that something is ‘a wellestablished fact’, you can be certain that they are voicing an opinion.

Adversarial conversation stops the truth from emerging. Arguing actually stops you exploring and discovering ideas. And the quality of the conversation rapidly worsens: people are too busy defending themselves, too frightened and too battlefatigued to do any better.

The Ladder of Inference

The Ladder of Inference is a powerful model that helps you move beyond argument. It was developed initially by Chris Argyris (see The Fifth Discipline Handbook, edited by Peter Senge et al, Nicholas Brealey, London, 1994). He pictures the way people think in conversations as a ladder. At the bottom of the ladder is observation; at the top, action.

- From your observation, you step on to the first rung of the ladder by selecting data. (You choose what to look at.)

- On the second rung, you infer meaning from your experience of similar data.

- On the third rung, you generalise those meanings into assumptions.

- On the fourth rung, you construct mental models (or beliefs) out of those assumptions.

- You act on the basis of your mental models.

You travel up and down this ladder whenever you hold a conversation. You are much better at climbing up than stepping down. In fact, you can leap up all the rungs in a few seconds. These ‘leaps of abstraction’ allow you to act more quickly, but they can also limit the course of the conversation. Even more worryingly, your mental models help you to select data from future observation, further limiting the range of the conversation. This is a ‘reflexive loop’; you might call it a mindset.

The Ladder of Inference gives you more choices about where to go in a conversation. It helps you to slow down your thinking. It allows you to:

- Become more aware of your own thinking

- Make that thinking available to the other person

- Ask them about their thinking

You May Also Need to Check:

Above all, it allows you to defuse an adversarial conversation by ‘climbing down’ from private beliefs, assumptions and opinions, and then ‘climbing up’ to shared meanings and beliefs.

The key to using the Ladder of Inference is to ask questions. This helps you to find the differences in the way people think, what they have in common and how they might reach shared understanding.

What’s the data that underlies what you’ve said?

- Do we agree on the data?

- Do we agree on what they mean?

- Can you take me through your reasoning?

- When you say [what you’ve said], do you mean [my rewording of it]?

For example, if someone suggests a particular course of action, you can carefully climb down the ladder by asking:

- ‘Why do you think this might work?’ ‘What makes this a good plan?’

- ‘What assumptions do you think you might be making?’ ‘Have you considered…?’

- ‘How would this affect…?’ ‘Does this mean that…?’

- ‘Can you give me an example?’ ‘What led you to look at this in particular?’

Even more powerfully, the Ladder of Inference can help you to offer your own thinking for the other person to examine. If you are suggesting a plan of action, you can ask:

- ‘Can you see any flaws in my thinking?’

- ‘Would you look at this stuff differently?’ ‘How would you put this together?’

- ‘Would this look different in different circumstances?’ ‘Are my assumptions valid?’

- ‘Have I missed anything?’

The beauty of this model is that you need no special training to use it. Neither does the other participant in the conversation. You can use it immediately, as a practical way to intervene in conversations that are collapsing into argument.

6. Summarise Often

Perhaps the most important of all the skills of conversation is the skill of summarising. Summaries:

- allow you to state your objective, return to it and check that you have achieved it

- help you to structure your thinking

- help you to manage time more effectively

- help you to seek the common ground between you

- help you to move beyond adversarial thinking

Simple summaries are useful at key turning points in a conversation. At the start, summarise your most important point or your objective. As you want to move on from one stage to the next, summarise where you think you have both got to and check that the other person agrees with you. At the end of the conversation, summarise what you have achieved and the action steps you both need to take.

To summarise means to reinterpret the other person’s ideas in your own language. It involves recognising the specific point they’ve made, appreciating the position from which they say it and understanding the beliefs that inform that position. Recognising what someone says doesn’t imply that you agree with it. Rather, it implies that you have taken the point into account. Appreciating the other person’s feelings on the matter doesn’t mean that you feel the same way, but it does show that you respect those feelings. And understanding the belief may not mean that you share it, but it does mean that you consider it important. Shared problem solving becomes much easier if those three basic summarising tactics come into play.

Of course, summaries must be genuine. They must be supported by all the non-verbal cues that demonstrate your recognition, appreciation and understanding. And those cues will look more genuine if you actually recognise, appreciate and – at least seek to – understand.

7. Use Visuals

It’s said that people remember about 20 per cent of what they hear, and over 80 per cent of what they see. If communication is the process of making your thinking visible, your conversations will certainly benefit from some way of being able to see your ideas.

There are lots of ways in which you can achieve a visual image of your conversation. The obvious ways include scribbling on the nearest bit of paper or using a flip chart. Less obvious visual aids include the gestures and facial expressions you make. Less obvious still – but possibly the most powerful – are word pictures: the images people can create in each other’s minds with the words they use.

Recording your ideas on paper

In my experience, conversations nearly always benefit from being recorded visually. The patterns and pictures and diagrams and doodles that you scribble on a pad help you to listen, to summarise and to keep track of what you’ve covered. More creatively, they become the focus for the conversation: in making the shape of your thinking visible on the page, you can ensure that you are indeed sharing understanding.

Recording ideas in this way – on a pad or a flip chart – also helps to make conversations more democratic. Once on paper, ideas become common property: all parties to the conversation can see them, add to them, comment on them and combine them.

What is really needed, of course, is a technique that is flexible enough to follow the conversation wherever it might go: a technique that can accommodate diverse ideas while maintaining your focus on a clear objective. If the technique could actually help you to develop new ideas, so much the better.

Fortunately, such a technique exists. It’s called mindmapping. Mindmaps are powerful first-stage thinking tools. By emphasising the links between ideas, they encourage you to think more creatively and efficiently.

Mindmaps are incredibly versatile conversational tools. They can help you in any situation where you need to record, assemble, organise or generate ideas. They force you to listen attentively, so that you can make meaningful connections; they help you to concentrate on what you are saying, rather than writing; and they store complicated information on one sheet of paper.

Try out mindmaps in relatively simple conversations to begin with. Record a phone conversation using a mindmap and see how well you get on with the technique. Extend your practice to face-to-face conversations and invite the other person to look at and contribute to the map.

A variation on mindmaps is to use sticky notes to record ideas. By placing one idea on each note, you can assemble the notes on a wall or tabletop and move them around to find logical connections or associations between them. This technique is particularly useful in brainstorming sessions or conversations that are seeking to solve complex problems.

Using Metaphors

Metaphors are images of ideas in concrete form. The word means ‘transferring’ or ‘carrying over’. A metaphor carries your meaning from one thing to another. It enables your listener to see something in a new way, by picturing it as something else.

Metaphors use the imagination to support and develop your ideas.

Metaphors bring your meaning alive in the listener’s mind. They shift the listener’s focus and direct their attention to what the speaker wants them to see. They stir their feelings. Metaphors can build your commitment to another person’s ideas and help you to remember them.

If you want to find a metaphor to make your thinking more creative and your conversation more interesting, you might start by simply listening out for them in the conversation you are holding. You will find you use many metaphors without even noticing them. If you are still looking, you might try asking yourself some simple questions:

• What’s the problem like?

• If this were a different situation – a game of cricket, a medieval castle, a mission to Mars, a kindergarten – how would I deal with it?

• How would a different kind of person manage the issue: a gardener, a politician, an engineer, a hairdresser, an actor?

• What does this situation feel like?

• If this problem were an animal, what species of animal would it be?

• How could I describe what’s going on as if it were in the human body?

Explore your answers to these questions and develop the images that spring to mind. You need to be in a calm, receptive frame of mind to do this: the conversation needs to slow down and reflect on its own progress. Finding metaphors is very much first-stage thinking, because metaphors are tools to help you see reality in new ways.

You will know when you’ve hit on a productive metaphor. The conversation will suddenly catch fire (that’s a metaphor!). You will feel a sudden injection of energy and excitement as you realise that you are thinking in a completely new way.

You May Also Need to Check: