Think of a presentation as a formal conversation. Speaking to groups is a notoriously stressful activity. Most people spend hours of their time holding conversations. Something strange seems to happen, however, when they’re called upon to talk to a group of people formally. A host of irrational – and maybe not so irrational fears – raise their ugly heads.

What do you fear most?

A recent study in the United States asked people about their deepest fears. The results were interesting. Here they are, in order:

- speaking to groups;

- heights;

- insects and bugs;

- financial problems;

- sickness;

- death;

- flying;

- loneliness;

- deep water;

- dogs.

(From The Book of Lists, David Wallechinsky)

I think that one of the main causes of this anxiety is that you put yourself on the spot when you present. The audience will be judging, not just your ideas and your evidence, but you as well. People may not remember reports or spreadsheets easily, but a presentation can make a powerful impression that lasts. If the presenter seemed nervous, incompetent or ill-informed, that reputation will stick – at least until the next presentation.

You, the presenter, are at the heart of it. An effective presenter puts themself centre-stage. An ineffective presenter tries to hide behind notes, a lectern, slides or computergenerated graphics. To become more effective, you need to take control of the three core elements of the event:

- the material;

- the audience;

- yourself.

Whatever you are presenting, you will also need to use all the skills of persuasion that we explored in Chapter 5:

- working out your big idea: your message;

- validating your message using SPQR (situation–problem–question–response, see Chapter 5);

- arranging your ideas coherently;

- expressing your ideas vividly;

- remembering your ideas;

- delivering well.

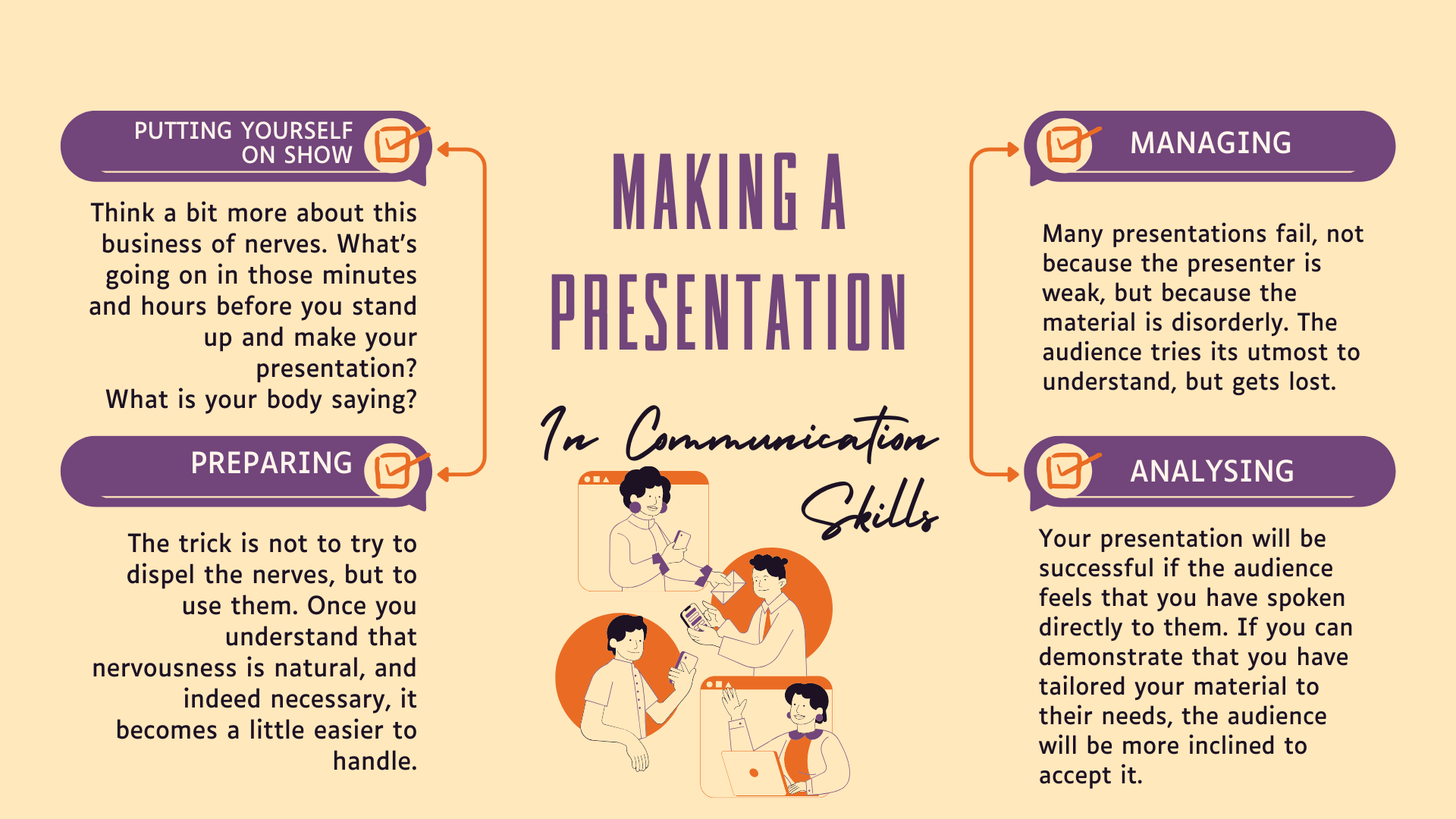

Putting yourself on show

Think a bit more about this business of nerves. What’s going on in those minutes and hours before you stand up and make your presentation? What is your body saying?

That nervous, jittery feeling is caused by adrenalin. This is a hormone secreted by your adrenal glands (near your kidneys). Adrenalin causes your arteries to constrict, which increases your blood pressure and stimulates the heart. Why stimulate the heart? To give you extra energy. When do you need extra energy? When you’re in danger. Adrenalin release is an evolved response to threat.

Adrenalin has two other effects. It increases your concentration – particularly useful when making a presentation. Less usefully, adrenalin also stimulates excretion of body waste. This decreases your body weight, giving you a slight advantage when it comes to running! That’s why you want to visit the toilet immediately before presenting.

Your anxiety is probably more about your relationship with the audience than about what you have to say. In the moments before you present, you may find yourself suffering from one or more of the following conditions:

- demophobia – a fear of people;

- laliophobia – a fear of speaking;

- katagelophobia – a fear of ridicule.

Check your condition against this list of adrenalin-related symptoms:

- rapid pulse;

- shallow breathing;

- muscle spasms in the throat, knees and hands;

- dry mouth;

- cold extremities;

- dilated pupils;

- sweaty palms;

- nausea.

And the worst of it is that, however much you suffer, the audience will forget virtually everything you say! That’s the bad news. The good news is that you’re not alone. Every presenter – indeed, every performer – suffers from nerves. Many actors and musicians talk about the horror of nerves and the fact that experience never seems to make them better.

The best news is that nerves are there to help you. They are telling you that this presentation matters – and that you matter. You are the medium through which the audience will understand your ideas. You should feel nervous. If you don’t, you aren’t taking the presentation seriously and you are in danger of letting your concentration slip.

Preparing for the Presentation

The trick is not to try to dispel the nerves, but to use them. Once you understand that nervousness is natural, and indeed necessary, it becomes a little easier to handle.

Everyone is frightened of the unknown. Any presentation involves an element of uncertainty, because it’s ‘live’. You can’t plan for the audience’s mood on the day. You may not even be able to foresee who will be there. You can’t plan for any sudden development that affects the proposal or explanation you are giving. You can’t plan for every question that you might be asked. This is, of course, the greatest strength of presentations: you and the audience are together, in the same place, at the same time. You are bringing the material alive for them, here and now. If nothing is left to chance, the presentation will remain dead on the floor.

The trick is to know what to leave to chance. If you can support your nerves with solid preparation, you can channel your nervous energy into the performance itself. Prepare well, and you will be ready to bring the presentation to life.

You can prepare in three areas:

- the material;

- the audience;

- yourself.

In each case, preparation means taking control. If you can remove the element of uncertainty in these areas, you will be ready to encounter what can’t be controlled: the instantaneous and living relationship between you and your audience.

Managing the Material

Many presentations fail, not because the presenter is weak, but because the material is disorderly. The audience tries its utmost to understand, but gets lost. You have to remember that they will forget virtually everything you say. They may remember rather more of what you show them, but only if it is quite simple. Don’t expect any audience to remember, from the presentation alone, more than half a dozen ideas.

In presentations, more than in any other kind of corporate communication, you must display the shape of your thinking. That shape will only be clear if you keep it simple. Detail doesn’t make things clearer; it makes things more complicated. If you want to display the shape of your thinking, you must design it. Managing the material is a design process (Figure 7.1).

Defining your Objective

Why are you making this presentation? That’s the first, and most important, question you must answer. Everything else – the material you include, its order, the level of detail you go into, how long the presentation will last, what visual aids you will use – will depend on your answer to this question.

What do you want your audience to take away at the end of do? Your objective is to tell them everything they need to know to

take that action – and nothing more.

Presentations are not for giving information. To repeat: your audience is probably going to forget almost all the information you give them. So packing the presentation full of information is almost certainly counterproductive. If you must offer your audience detailed information, put it in supporting notes.

I believe that there’s only one reason why you should be making a presentation. It may sound rather grand, but a presentation should inspire your audience. They want to be interested: to be moved, involved, intrigued. Your task is to bring your ideas alive with your own feelings, commitment and passion. You can demonstrate this commitment further when the audience asks you questions. It’s your conviction that the audience is looking for.

So your objective must be to inspire your audience. If you have any other objective, choose another method of communication. If you are simply making a pronouncement and not seeking or expecting any kind of response, you may as well write it down. For teaching or instructing, you will need to adapt a presentation into a much more interactive activity.

Write your objective down in one sentence. This helps you to:

- clear your mind;

- select material to fit;

- check at the end of planning that you are still addressing a single clear issue.

Write a simple sentence beginning:

- ‘The aim of this presentation is to…’

Make sure the verb following that word ‘to’ is suitably inspirational!

Analysing your Audience

Your presentation will be successful if the audience feels that you have spoken directly to them. If you can demonstrate that you have tailored your material to their needs, the audience will be more inclined to accept it.

So think about your audience carefully:

- How many will there be?

- What is their status range?

- Will they want to be there?

- How much do they already know about the matter? How much more do they need to know?

- What will they be expecting? What is the history, the context, the rumour, the gossip?

- How does your message and your material relate to the audience? Relevance defines what you will research, include and highlight. It will also help you to decide where to start: what your point of entry will be.

- Is the audience young or old? Are they predominantly one gender or mixed?

- Are they technical specialists or generalists? They will want different levels of detail.

- Where are they in the organisation? Different working groups will have different interests and different ways of looking at the world.

Think, too, about the audience’s expectations of the presentation. They may see presentations often, or very rarely. They may also have specific expectations of you, the presenter: they may know you well or hardly at all; you may have some sort of reputation that goes before you.

Constructing a Message

Once you have your objective, and you have some sense of who your audience is, you can begin to plan your material. Begin with a clear message. This should have all the characteristics of the messages that we looked at in Chapter 5. Your message must:

- be a sentence;

- express your objective;

- contain a single idea;

- have no more than 15 words;

- grab your audience’s attention.

You might consider putting this message on to a slide or other visual aid and show it near the start of the presentation. But an effective message should stick in the mind without any help. Make your message as vivid as you can.

Creating a Structure

Everything in the structure of the presentation should

support your message. Keep the structure of your presentation

simple. The audience will forget most of what you say to them.

Make sure that they remember your message and a few key

points.

Weaving an Introduction

Use SPQR to start the presentation, leading the audience

from where they are to where you want them to be. This also

allows you to show that you understand their situation and that

you are there to help them. Using SPQR will convince them that

you have put yourself into their shoes. The more obvious the

problem is to the audience, the less time you will need to spend

on SPQR.

SPQR also allows you to demonstrate your own credentials

for being there. (Look back at the notes on ethos in Chapter 5.)

Your values and beliefs are what make you credible to the

audience: remember, they are judging you as well as what you

have to say. What qualifies you to speak on this subject? What

special experience or expertise do you have? How can you add

value to the ideas in your presentation?

Your own values and beliefs will be more credible if you can

weave them into a story. SPQR gives you the structure. You could

begin your presentation by telling a brief story, making sure that

your audience will be able to relate to it. Stories have a way of

sticking in the mind long after arguments have faded. Choose a

story that demonstrates your values in relation to the matter in

hand. Beware generalised sentiment. Avoid ‘motherhood and

apple pie’ stories. Make the story authentic and relevant. And

keep it brief. You need to allow as much time as possible for your

new ideas.

Building a Pyramid

Use a pyramid structure to outline your small number of key

points. Show the pyramid visually: overhead or PowerPoint

slides, or a flip chart. Indicate that these key points will form the

sections of the presentation.

Repetition is an essential feature of good presentations.

Because the audience can’t reread or rewind to remind

themselves of what you said, you need to build their recall by

repeating the key features of your presentation. The key features

will be your message, your structure, your key points and any

call to action that you deliver at the end. Aim to build the

audience’s recall on no more than about half-a-dozen pieces of

information.

Most people seem to know the famous tell ’em principle:

• Tell ’em what you’re going to tell ’em.

• Tell ’em.

• Tell ’em what you’ve told ’em.

This valuable technique is one you should use often in your

presentation. Build the three-part repetition into the

presentation as a whole: tell ’em at the start what the whole

presentation will cover; and tell ’em at the end what the whole

thing has covered. Use the technique, too, within each part of the

presentation: summarising at the start and end, so that you lead

the audience into and out of each section explicitly.

Don’t be afraid to repeat your ideas. If you want the audience

to remember them, you can’t repeat them too often.

If you plan well, you will almost certainly create too much

material. You must now decide what to leave out, and what you

could leave out if necessary. Be ruthless. Bear in mind that your

audience will forget most of what you say. Go back to your

pyramid and make sure that you have enough time to cover each

key point. Weed out any detail that will slow you down or divert

you from your objective.

Opening and Closing the Presentation

Once the body of the presentation is in place, you need to

design an opening and close that will help you take off and land

safely. You need to be able to perform these on ‘autopilot’.

Memorise them word for word or write them out in full.

The opening of your presentation should include:

• introducing yourself – who you are and why you are there;

• acknowledging the audience – thanking them for their time and recognising what they are expecting;

• a clear statement of your objective or, better still, your message;

• a timetable – finish times, breaks if necessary;

• rules and regulations – note-taking, how you will take questions;

• any ‘housekeeping’ items – safety, refreshments, administration.

Once these elements are in place, you can decide exactly how to

order the items. You might decide to start with something

surprising or unusual: launching into a story or a striking

example, seemingly improvising some remark about the venue or

immediate circumstances of your talk, asking a question.

Sometimes it’s a good idea to talk with the audience at the very

start before launching into the presentation proper.

The close of the presentation is the most memorable

moment. Whatever else happens, the audience will almost

certainly remember this! This is your last chance to ‘tell ’em what

you’ve told ’em.’ Summarise your key points, and your message.

Give a call to action. Add feeling: this is the place for you to

invoke pathos. (Look back at the start of Chapter 5 for more on

this.) Be specific in your call to action: what exactly do you want

the audience to do?

Thank the audience for their attention. You might also

formally guide them into a question session, giving them time to

relax after concentrating and perhaps pre-arranging a ‘planted

question’ in the audience to set the ball rolling.

Putting it on Cards

Put your ideas on to cards. These are useful memory devices and will help you to bring the presentation alive.

The best presentations are given without notes. But few people will always have the confidence or experience to be able to deliver without any help. Nevertheless, any notes you create should aim to support your memory, not substitute for it.

Don’t write your presentation out in full unless you are an accomplished actor. Only actors can make recitation sound convincing – and nobody is asking you to act. Use cards. Filing or archive cards are best; use the largest you can find. Cards have a number of key advantages.

• They are less shaky than paper – they don’t rustle.

• They are more compact.

• They give your hands something firm to hold.

• They can be tagged with a treasury tag to prevent loss of order.

• They look more professional.

• They force you to write only brief notes.

By writing only brief notes, triggers and cues on your cards, you force yourself to think about what you are saying, while you are saying it. This means that you will sound much more convincing. Obviously, your audience will only tolerate a certain amount of silence while you think of the next thing to say. The note on the card is there to trigger that next point and keep you moving.

Write your notes in bold print, using pen or felt-tip. Write on only one side and number the cards sequentially. Include:

• what you must say;

• what you should say to support the main idea;

• what you could say if you have time.

Add notes on timing, visual aids, cues for your own behaviour. Keep the cards simple to look at and rehearse with them so that you get to know them.

Adding Spice

Exciting presentations bring ideas alive. You are the medium

through which the audience understands the material. You must

make the presentation your own and give it the spicy smell of

real life.

Rack your brain for anything you can use. Think it up, cook it

up, dream it up if necessary. Look for:

• images;

• examples;

• analogies;

• stories;

• pictures;

• jokes (but be very careful about these).

The aim is to create pictures in your audience’s mind. Don’t let

computer graphics do it all for you. And don’t fall into the trap of

thinking that putting text on a visual aid makes it visual. Your

audience wants images: real pictures, not words.

The most powerful pictures are the ones you can conjure up

in your audience’s imagination with your own words. There’s a

famous story about a little girl who claimed she liked plays on the

radio, ‘because the pictures were better’. You should be aiming to

create such pictures in your audience’s mind.

Designing visuals

Working on the visuals can take longer than any other part of

planning. The important thing to remember is that any aid you

use is there to help you, not to substitute for you. You are not a

voice-over accompanying a slide presentation; the pictures are

there to illustrate your ideas. The audience wants to see you: to

meet with you, assess you, ask you questions, learn about you.

They will not have the chance to do any of this if you hide behind

your visual aids.

Visual aids intrude. The moment you turn on the projector or

turn to the flipchart, the audience’s attention is on that rather

than you. A small number of excellent visual aids will have far

more impact than a large number of indifferent ones. Don’t fall

into the trap of thinking that every part of the presentation

should have an accompanying slide.

Make your visuals just that: visual. If you can avoid using

words, do so. How can you put the information into graphic

form? Is there a picture you can use to illustrate or suggest what

you are saying? Words are for listening to. Visual aids are for

looking at. It really is that simple.

6 × 6 × 6

If you must put words on your slides, they should obey this design principle.

No more than six lines of text on any slide.

No more than six words on any one line.

The text should be visible on a laptop screen from a distance of six metres. (For most fonts, this means a minimum size of about 24pt.)

Audiences’ expectations of slides are changing. We all know that

it’s quite easy to produce slides with flashy animation. Many

people are becoming bored with endless slide shows filled with

more or less poorly designed slides. Confound your audience’s

expectations. Use the technology by all means – and then leap

away from it, galvanising your audience with your own passion

for your subject. Or be really daring, and work without any slides

at all.

Rehearsing

There is a world of difference between thinking your presentation through and doing it. You may think you know what you want to say, but until you say it you don’t really know. Only by uttering it aloud can you test whether you understand what you are saying. Rehearsal is the reality check.

Rehearsal is also a time check. Time acts oddly in presentations. It can seem to stop, to drag and – more often than not – to race away. The most common time problem I encounter with trainees who are rehearsing their presentations is that they run out of time. They are astounded when I tell them that time is up and they have hardly finished introducing themselves! You must rehearse to see how long it all takes. Be aware that it will probably take longer than you anticipate: maybe 50 per cent longer.

The ultimate aim of rehearsal is to give you freedom in the

presentation itself. Once you have run through the presentation a

few times, you will be able to concentrate on the most important

element of the event; your relationship with the audience.

Under-rehearsed presenters spend too much time working out

what to say. Well-rehearsed presenters know what to say and can

improvise on it according to the demands of the moment.

Try to think of each presentation as brand new. After all, it’s

probably new for this particular audience. They haven’t heard

your stories or arguments before. They are going on this journey

for the first time. Change the material a little each time you

present. Think of a new story or a new example.

You must also rehearse with any equipment that you intend

to use. Nothing is more nerve-wracking than trying to present

with a projector or laptop you’ve never seen before. Rehearse also

to improve your use of the equipment:

• Talk without support. Don’t use the visuals as a crib.

• Don’t talk to visuals. They can’t hear you. Avoid turning your back on the audience.

• Rehearse in real time: don’t skip bits.

• Rehearse with a friend. Ask them what they think and work with them to improve.

• Rehearse with your notes. Get into the habit of looking up from them.

• Rehearse with the visual aids at least once.

• Rehearse in the venue itself if you can. If you can’t, try to spend some time there, getting the feel of the room.

• Don’t let the light of the visuals put you in darkness.

• Make sure you know how to put things right if they go wrong.

• If you can, be ready to present without any visual aids at all.

Controlling the Audience

Many presenters concentrate so hard on the material that they ignore the audience. They have no idea of the messages that their body is sending out. They are thinking so hard about what they are saying that they have no time to think about how they say it.

You are performing. Your whole body is involved. You must become aware of what your body is doing so that you can control it, and thus the audience. A few basic principles will ensure that you keep the audience within your control.

Eye Contact

You speak more with your eyes than with your voice. Your eyes

tell the audience that you are taking notice of them, that you are

confident to speak to them, that you know what you are talking

about and that you believe what you are saying.

Look at the audience’s eyes throughout the presentation.

Imagine that a lighthouse beam is shooting out from your eyes

and scanning the audience. Make sure that the beam enters every

pair of eyes in the room. Focus for a few seconds on each pair of

eyes and meet their gaze. Don’t look past them, through them or

over their heads. Pick out a few faces that look particularly

friendly and return to them. After a while, you may even feel

confident enough to return to a few of the less friendly ones!

Include the whole audience with your eyes. Many presenters

fall into the trap of focusing on only one person: the most senior

manager, the strongest personality, maybe simply someone they

like a lot.

Keep your cue cards in your hand so that you can easily

glance down at them and bring your eyes back to the audience

quickly

Your face

The rest of your face is important, too! Remember to smile.

Animate your face and remember to make everything just a little

larger than life so that your face can be ‘read’ at the back of the

room.

Gestures

Many presenters worry about how much or little they gesture.

This is reasonable. Arms and hands are prominent parts of the

body and can sometimes get out of control.

The important thing is to find the gestures that are natural for

you. If you are a great gesticulator, don’t try to force your hands

into rigid stillness. If you don’t normally gesture a great deal,

don’t force yourself into balletic movements. Use your hands to

paint pictures and to help you get the words out. Keep your

gestures open, away from your body and into the room. Don’t

cross your hands behind your back or in front of your crotch, and

don’t put them in your pockets too much. (It’s a good idea to

empty your pockets before the presentation so that you don’t find

yourself jingling coins or keys.)

Movement

Aim for stillness. This doesn’t mean that you should stand

completely still all the time. Moving about the room shows that

you are making the space your own, and helps to energise the

space between you and the audience. But rhythmic, repetitive

movement can be annoying and suggest the neurotic pacing of a

panther in a cage. Try not to rock on your feet or tie your legs in

knots! Aim to have both feet on the ground as much as possible

and slow down your movements.

It can sometimes help to sit to present. You might practise

with a chair, or the back of a chair, a stool or even the edge of a

table. Make sure that it is stable and solid enough to bear your

weight!

Looking after Yourself

And you will still be nervous as the moment of truth approaches. Remember that those nerves are there to help you. If you have prepared adequately, you should be ready to use them to encounter the uncertainty of live performance.

You certainly need time before presenting that is quiet and focused. I need to spend about 15 minutes doing nothing but preparing myself mentally. I put myself where nothing can distract me from the presentation. Visualising success immediately before the presentation works for some people. Ahead of time, imagine yourself presenting, the audience attentively listening to your every word, applauding you at the end and asking keen questions afterwards.

On some occasions it can be useful to meet the audience and chat with them before you start. This can break the ice and put you more at ease. In truth, I rarely feel comfortable doing this; for others, it can be highly beneficial in relaxing them and preparing for the presentation.

The most important preparation involves breathing. Make contact with the deepest kind of breathing, which works from the stomach rather than the upper part of the lungs. Slow that breathing down, and make it calm, regular and strong. This works wonders for the voice: it gives it depth and power, and makes for a more convincing delivery.

Along with your breathing, pay attention to the muscles around your mouth that help you to articulate. Try some tonguetwisters or sing a favourite song. Chew the cud, and get your tongue and lips really working and warmed up. A very simple exercise is to stick your tongue as far out of your mouth as you can and then speak a part of your presentation, trying to make the consonants as clear as you can. You only need to do this for about 30 seconds to wake up your voice and make it clearer. You will, of course, look rather silly while doing this, so it’s best to do the exercise in a private place!

Answering Questions

Many presenters are as worried about the question session as about the presentation itself. A few guidelines can help to turn your question session from a trial into a triumph:

• Decide when to take questions. This will probably be at the end. But you might prefer to take questions during the presentation. This is more difficult to manage but can improve your relationship with the audience.

• Anticipate the most likely questions. These may be ‘Frequently Asked Questions’ that you can easily foresee. Others may arise from the particular circumstances of the presentation.

• Use a ‘plant’. Ask somebody to be ready with a question to start the session off. Audiences are sometimes hesitant at the end of a presentation about breaking the atmosphere.

• Answer concisely. Force yourself to be brief.

• Answer honestly. You can withhold information, but don’t lie. Someone in the audience will almost certainly see through you.

• Take questions from the whole audience. From all parts of the room and from different ‘social areas’.

• Answer the whole audience. Don’t let questions seduce you into private conversations. Make sure the audience has heard the question.

• If you don’t know, say so. And promise what you’ll do to answer later.