In previous article, we learn basic rules of communication skills. In this article, we will talk about how conversations work? in the English language. Conversation is our primary management tool. We converse to build relationships with colleagues and customers. We influence others by holding conversations with them. We converse to solve problems, to co-operate and find new opportunities for action. Conversation is our way of imagining the future.

It may be good to talk, but conversations at work are often difficult. A manager summed up the problem to me recently. ‘If we don’t re-learn how to talk with each other,’ he said, ‘frequently and on a meaningful level, this organisation won’t survive.

In this article we will talk about:

- How conversations work?

- What is a conversation?

- Why do conversations go wrong?

- Putting conversations in context

- Working out the relationship

- Setting a structure

- Managing behavior

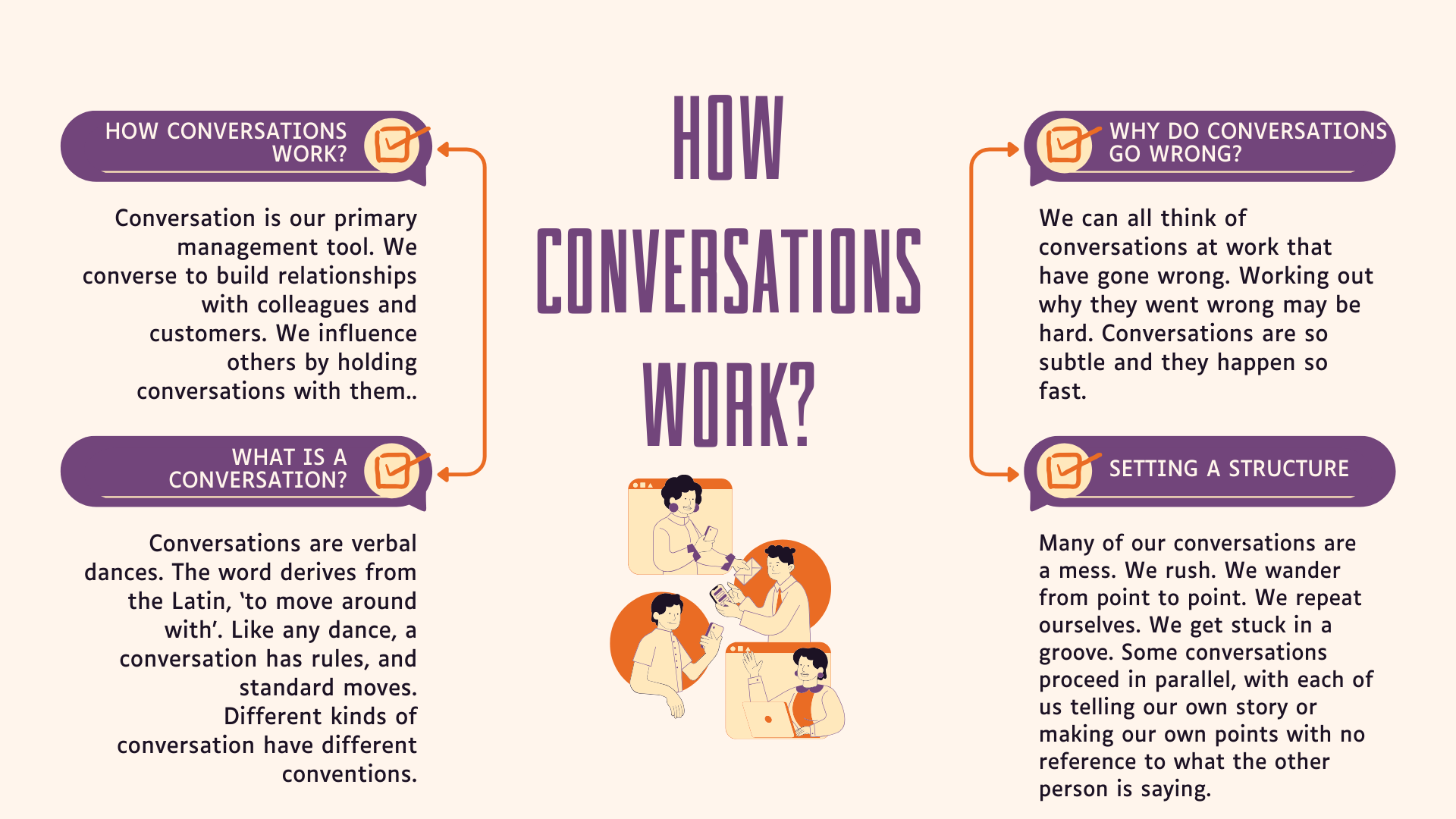

How conversations work?

Conversation is our primary management tool. We converse to build relationships with colleagues and customers. We influence others by holding conversations with them. We converse to solve problems, to co-operate and find new opportunities for action. Conversation is our way of imagining the future.

It may be good to talk, but conversations at work are often difficult. A manager summed up the problem to me recently. ‘If we don’t re-learn how to talk with each other,’ he said, ‘frequently and on a meaningful level, this organisation won’t survive.’

What is a conversation?

Conversations are verbal dances. The word derives from the Latin, ‘to move around with’. Like any dance, a conversation has rules, and standard moves. These allow people to move more harmoniously together, without stepping on each other’s toes or getting out of step. Different kinds of conversation have different conventions. Some are implicitly understood; others, for example in presentations or meetings, must be spelt out in detail

and rehearsed.

A conversation is a dynamic of talking and listening. Without the listening, there’s no conversation. And the quality of the conversation depends more on the quality of the listening than on the quality of the speaking.

Why do conversations go wrong?

We can all think of conversations at work that have gone wrong. Working out why they went wrong may be hard. Conversations are so subtle and they happen so fast. Few of us have been trained in the art of effective conversation. Conversation is a life skill, and – like most life skills – one that we are usually expected to pick up as we go along.

Broadly, there are four main areas where conversations can fail:

• Context

• Relationship

• Structure

• Behaviour

These are the four dimensions of conversation. By looking at them, we can begin to understand more clearly how conversations work, why they go wrong, and how we can begin to improve them.

Putting conversations in context

All conversations have a context. They happen for a reason. Most conversations form part of a larger conversation: they are part of a process or a developing relationship. Many conversations fail because one or both of us ignore the context. If we don’t check that we understand why the conversation is happening, we may very quickly start to misunderstand each other.

The problem may simply be that the conversation never happens. One of the most persistent complaints against managers is that they are not there to talk to: ‘I never see him’, ‘She has no idea what I do’, ‘He simply refuses to listen’. Other obvious problems that afflict the context of the conversation include:

- not giving enough time to the conversation;

- holding the conversation at the wrong time;

- conversing in an uncomfortable, busy or noisy place;

- a lack of privacy;

- distractions.

Less obvious, but just as important, are the assumptions that we bring to our conversations. All conversations start from assumptions. If we leave them unquestioned, misunderstandings and conflict can quickly arise. For example, we might assume that:

- we both know what we are talking about;

- we need to agree;

- we know how the other person views the situation;

- we shouldn’t let our feelings show;

- the other person is somehow to blame for the problem;

- we can be brutally honest;

- we need to solve the other person’s problem;

- we’re right and they’re wrong.

These assumptions derive from our opinions about what is true, or about what we – or others – should do. We bring mental models to our conversations: constructions about reality that determine how we look at it. For example, I might hold a mental model that we are in business to make a profit; that women have an inherently different management style from men; or that character is determined by some set of national characteristics.

Millions of mental models shape and drive our thinking, all the time. We can’t think without mental models. Thinking is the process of developing and changing our mental models.

All too often, however, conversations become conflicts between these mental models. This is adversarial conversation, and it is one of the most important and deadly reasons why conversations go wrong.

Working out the Relationship

Our relationship defines the limits and potential of our conversation. We converse differently with complete strangers and with close acquaintances. Conversations are ways of establishing, fixing or changing a relationship.

Relationships are neither fixed nor permanent. They are complex and dynamic. Our relationship operates along a number of dimensions, including:

- Status

- Power

- Role

- Liking

All of these factors help to define the territory of the conversation.

-

Status

We can define status as the rank we grant to another person in relation to us. We normally measure it along a simple (some might say simplistic) scale. We see ourselves simply as higher or lower in status in relation to the other person.

We confer status on others. It’s evident in the degree of respect, familiarity or reserve we grant them. We derive our own sense of status from the status we give the other person. We do all this through conversation.

Conversations may fail because the status relationship limits what we say. If we feel low in status relative to the other person, we may agree to everything they say and suppress strongly held ideas of our own. If we feel high in status relative to them, we may tend to discount what they say, put them down, interrupt or ignore them. Indeed, these behaviours are ways of establishing or altering our status in a relationship.

Our status is always at risk. It is created entirely through the other person’s perceptions. It can be destroyed or diminished in a moment. Downgrading a person’s status can be a powerful way of exerting your authority over them.

-

Power

Power is the control we can exert over others. If we can influence or control people’s behaviour in any way, we have power over them. John French and Bertram Raven (in D Cartwright (ed) Studies in Social Power, 1959), identified five kinds of power base:

- reward power: the ability to grant favours for behaviour;

- coercive power: the ability to punish others;

- legitimate power: conferred by law or other sets of rules;

- referent power: the ‘charisma’ that causes others to imitate or idolise;

- expert power: deriving from specific levels of knowledge or skill

Referent power is especially effective. Conversations can become paralysed as one of us becomes overcome by the charisma of the other.

Conversations often fail because they become power struggles. People may seek to exercise different kinds of power at different points in a conversation. If you have little reward power over the other person, for example, you may try to influence them as an expert. If you lack charisma or respect with the other person, you may try to exert authority by appealing to legitimate or to coercive power.

-

Role

A role is a set of behaviours that people expect of us. A formal role may be explicitly defined in a job description; an informal role is conferred on us as a result of people’s experience of our conversations.

Conversations may fail because our roles are unclear, or in conflict. We tend to converse with each other in role. If the other person knows that your formal role is an accountant, for example, they will tend to converse with you in that role. If they know that your informal role is usually the devil’s advocate, or mediator, or licensed fool, they will adapt their conversation to that role. Seeing people in terms of roles can often lead us to label them with that role. As a result, our conversations can be limited by our mental models about those roles.

-

Liking

Conversations can fail because we dislike each other. But they can also go wrong because we like each other a lot!

The simple distinction between liking and disliking seems crude. We can find people attractive in many different ways or take against them in ways we may not be able – or willing – to articulate. Liking can become an emotional entanglement or even a fully-fledged relationship; dislike can turn a conversation into a vendetta or a curious, half-coded game of tit-for-tat.

These four factors – status, power, role and liking – affect the territorial relationship in the conversation. A successful conversation seeks out the shared territory, the common ground between us. But we guard our own territory carefully. As a result, many conversational rules are about how we ask and give permission for the other person to enter our territory.

The success of a conversation may depend on whether you give or ask clearly for such permission. People often ask for or give permission in code; you may only receive the subtlest hint, or feel inhibited from giving more than a clue of your intentions. Often, it’s only when the person reacts that you realise you have intruded on private territory.

Setting a Structure

Many of our conversations are a mess. We rush. We wander from point to point. We repeat ourselves. We get stuck in a groove. Some conversations proceed in parallel, with each of us telling our own story or making our own points with no reference to what the other person is saying. If conversation is a verbal dance, we often find ourselves trying to dance two different dances at the same time, or treading on each other’s toes.

Why should we worry about the structure of our conversations? After all, conversations are supposed to be living and flexible. Wouldn’t a structure make our conversation too rigid and uncomfortable?

Maybe. But all living organisms have structures. They cannot grow and develop healthily unless they conform to fundamental structuring principles.

Conversations, too, have structural principles. The structure of a conversation derives from the way we think. We can think about thinking as a process in two stages.

First-stage thinking is the thinking we do when we are looking at reality. First-stage thinking allows us to recognise something because it fits into some pre-existing mental pattern or idea. Ideas allow us to make sense of reality. The result of first-stage thinking is that we translate reality into language. We name an object or an event; we turn a complicated physical process into an equation; we simplify a structure by drawing a diagram; we contain a landscape on a map.

Second-stage thinking manipulates the language we have created to achieve a result. Having named something as, say, a cup, we can talk about it coherently. We can judge its effectiveness as a cup, its value to us, how we might use it or improve its design. Having labelled a downturn in sales as a marketing problem, we explore the consequences in marketing terms.

Our conversations all follow this simple structure. We cannot talk about anything until we have named it. Conversely, how we name something determines the way we talk about it. The quality of our second-stage thinking depends directly on the quality of our first-stage thinking.

We’re very good at second-stage thinking. We have lots of experience in manipulating language. We’re so good at it that we can build machines to do it for us: computers are very fast manipulators of binary language.

We aren’t nearly so good at first-stage thinking. We mostly give names to things without thinking. The cup is obviously a cup; who would dream of calling it anything else? The marketing problem is obviously a marketing problem – isn’t it? As a result, most of our conversations complete the first stage in a few seconds. We leap to judgement.

Suppose we named the cup as – to take a few possibilities at random – a chalice, or a vase, or a trophy. Our second-stage thinking about that object would change radically. Suppose we decided that the marketing problem might be a production problem, a distribution problem, or a personnel problem. We would start to think very differently about it at the second stage.

We prefer to take our perceptions for granted. But no amount of second-stage thinking will make up for faulty or limited first-stage thinking. Good thinking pays attention to both stages. Effective conversations have a first stage and a second stage.

An effective conversation manages structure by:

- Separating the two stages

- Checking that we both know what stage we are in

- Asking the questions appropriate to each stage

Managing Behaviour

Conversations are never simply exchanges of words. Supporting the language we use is a whole range of non-verbal communication: the music of our voice, the gestures we use, the way we move our eyes or hold our body, the physical positions we adopt in relation to each other.

We have less control over our non-verbal behaviour than over the way we speak. This may be because we have learnt most of our body language implicitly, by absorbing and imitating the body language of people around us. Our non-verbal communication will sometimes say things to the other person that we don’t intend them to know. Under pressure, our bodies leak information. Our feelings come out as gestures.

Conversations often go wrong because we misinterpret nonverbal messages. There are four main reasons for this:

- Non-verbal messages are ambiguous. No dictionary can accurately define them. Their meaning can vary according to context, to the degree of intention in giving them, and because they may not consistently reflect feeling.

- Non-verbal messages are continuous. We can stop talking but we can’t stop behaving! Language is bound by the structures of grammar. Non-verbal communication is not structured in the same way.

- Non-verbal messages are multi-channel. Everything is happening at once: eyes, hands, feet, body position. We interpret non-verbal messages holistically, as a whole impression. This makes them strong but unspecific, so that we may not be able to pin down exactly why we get the impression we do.

- Non-verbal messages are culturally determined. Research suggests that a few non-verbal messages are universal: everybody seems to smile when they are happy, for example. Most non-verbal behaviours, however, are specific to a culture. A lot of confusion can arise from the misinterpretation of non-verbal messages across a cultural divide.

Effective communicators manage their behaviour. They work hard to align their non-verbal messages with their words. You may feel that trying to manage your own behaviour in the same way is dishonest: ‘play-acting’ a part that you don’t necessarily feel. But we all act when we hold conversations. Managing our behaviour simply means trying to act appropriately.

The most important things to manage are eye contact and body movement. By becoming more conscious of the way you use your eyes and move your limbs, you can reinforce the effect of your words and encourage the other person to contribute more fully to the conversation. Simple actions like keeping your limbs and hands still, or looking steadily at the speaker while they are speaking, can make a big and immediate difference to the quality of the conversation.

You May Also Need to Check: